FAKE FAKE FAKE

2021

The state of the world today tethers at an edge. A world locked down by a pandemic that has killed over 1.5 million, affected 68 million worldwide, numbers rivaling the Spanish flu in 1918. Airline companies have lost a collective 118 billion USD with 46 million jobs at risk. What we know about the world has changed, leading to perceivable seismic shifts. Under movement restrictions, internet usage has soared. The big tech companies have risen USD 160 billion in market capitalization during the pandemic, while the wealth of Jeff Bezos, the world’s richest man, increased by USD 90 billion. In a period of lockdown and safety measures, we have seen riots break out across America along the lines of racial violence, partisan politics, class divide, and mask usage. Relativism has been put out into full view. Fact is no longer agreed upon; science and expert views are filtered through the lens of ideological differences and spread through the platforms of social media, traditional media, and phishing accounts.

Fake news isn’t new.

In the 13th century BCE, Ramses the Great spread propaganda through temple murals and court poetry depicting his victory in Kadesh. The Egyptian-Hittite peace treaty thereafter and his private correspondence however revealed he did not win that battle. Disinformation in its current form is a multifaceted strategy played at the expense of the society through nation actors, geopolitics, and global dominance. And as described by Professor Cherian George, a leading academic on hate propaganda and media freedom, “Disinformation campaigns are primarily made up of distortion that doesn’t need lies.” FAKE FAKE FAKE is a visual map of our reflections and thoughts over the historical and future relevance of information and identity. A miner’s canary in a world at the tipping point of dissecting fact into fiction.

ARTIFACT 01

2021 | Video | 01:06

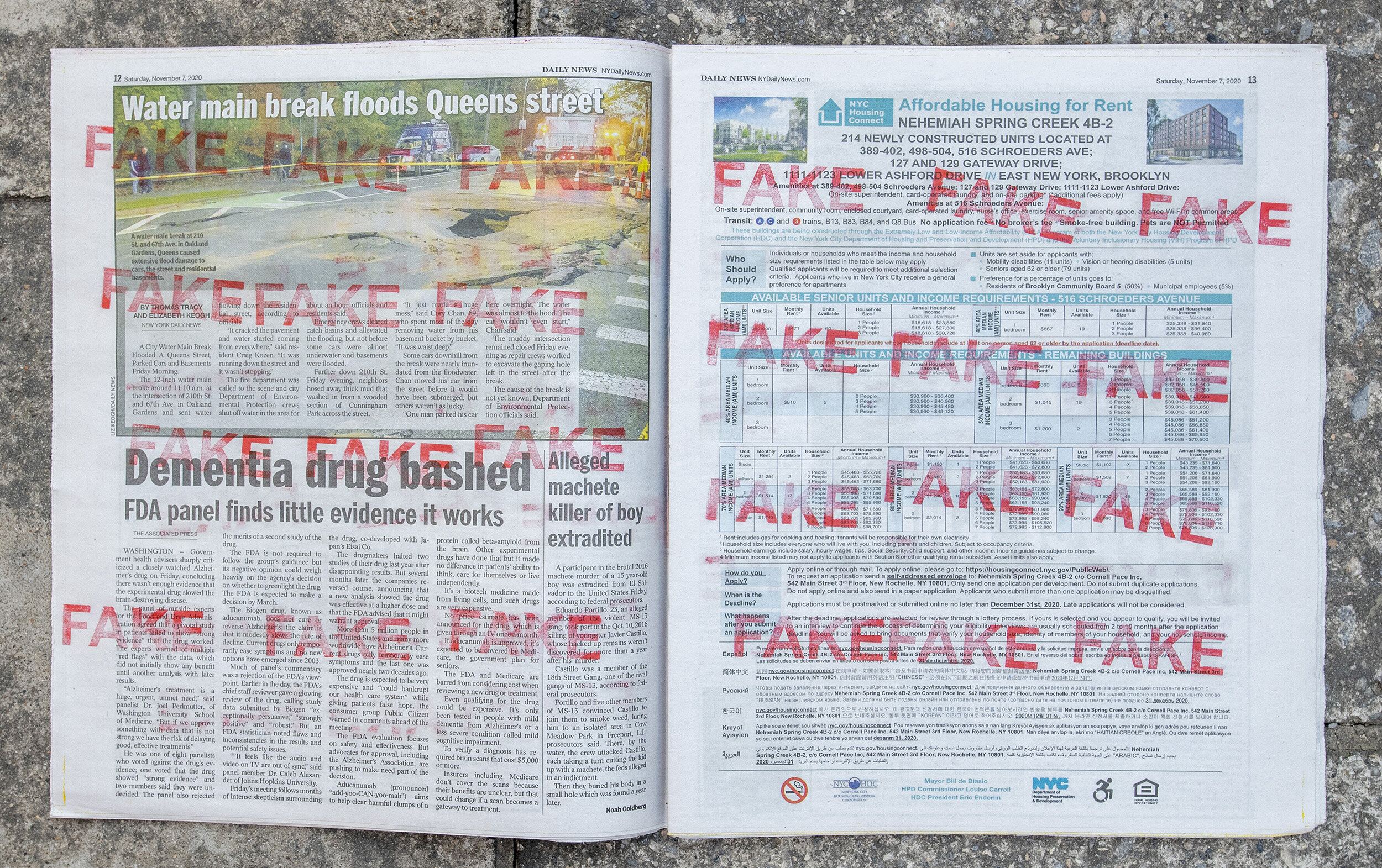

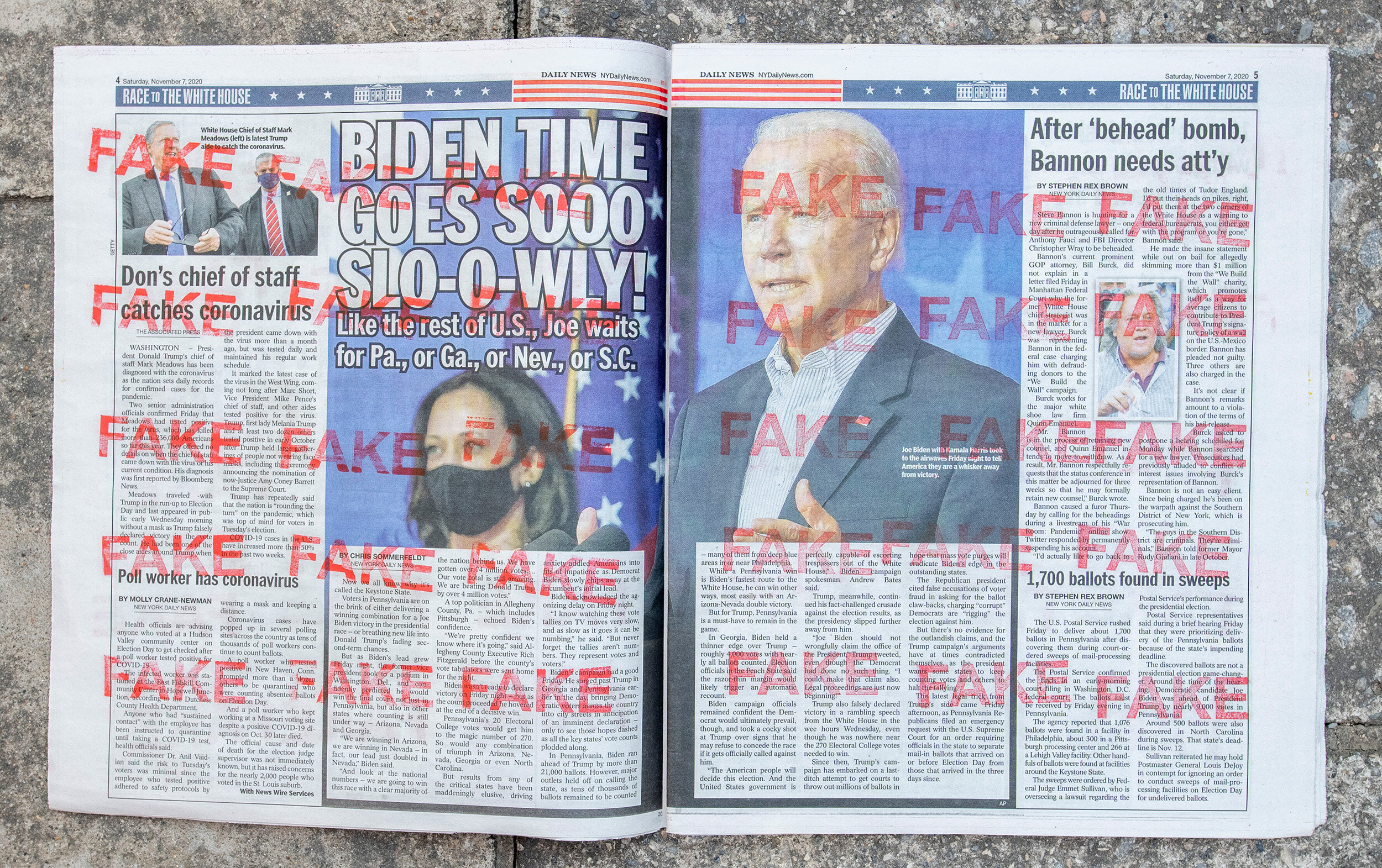

ARTIFACT 02

2021 | Newspapers, Red Ink Stamp | Various Dimensions

ARTIFACT O3

2021 | Video | 1:00

+ ARTIFACT 04 2020 | Academic Interview

Interview with Professor Cherian George, Associate Dean (Research and Development), School of Communication, Hong Kong Baptist University

Date of interview: December 3, 2020

About Cherian George: Professor George’s professional life has been devoted to journalism practice, education, research and advocacy. A native of Singapore, he worked as a journalist for the Straits Times before moving into academia. His academic research centres on freedom of expression, and hate propaganda. Prof. George received his Ph.D. in Communication from Stanford University. He has a Masters from Columbia University’s School of Journalism and a B.A. in Social and Political Sciences from Cambridge University.

Abbreviations: CG – Cherian George HYL – Huiyi Lin (Chow and Lin)

Interview Transcript

HYL: Thank you very much for agreeing to the interview today, we are doing research leading up to our show at Extraperlo which will be in Madrid next year. And today we would like to explore with your understanding of the topic of fake news, and how it affects society and politics, what are the ramifications on a global scale. And given that you are an expert in this area, specifically, on the Asia perspective. Please feel free to correct me in any parts that I am mistaken and also give examples that you think are necessary to show the impact and implications. And also the relationship with media - how you see the role of media.

CG: Well, in any society that is larger than a few hundred, citizens will never get to know their neighbours who will be strangers and yet are part of their own society. Besides that, in an age of globalization, there's so much that affects us, and again we will never get to know directly. So at this most basic level we can think of media as a kind of almost “super” sense. It is a sense that allows us to go beyond what our own eyes and ears are able to capture. It tells us about the world, the ways in which things far beyond what we can see and hear will affect us. And conversely the ways in which ourselves as consumers and citizens affect the lives of others. It brings us into conversation with people who are maybe very different from us and ordinarily we would not have any chance to get to know. And this of course is essential for a healthy society because in any large society, not everybody is like us, and coping with diversity is a key part of what media can help us with. From a democratic point of view the media is essential for citizens to keep an eye on those who rule over us. It is essential to help us develop and communicate public opinion, so this is quite integral to the functioning of a healthy society.

HYL: Yes. Leading on from that, what do you think is the relationship between government, media and the people?

CG: On the bright side, if we take a long historical view, governments can no longer achieve legitimacy in total darkness. There is an expectation, even in non-democratic countries on the things that governments do need to be subject to the light of publicity, there needs to be a certain buy-in from citizens. All of this can only be done with a media that is independent enough to scrutinized, so there's a shift in expectations… Governments no longer get to say that, we're in charge because we were born to rule, or that we have some God-given right to rule over you. Legitimacy is important and media is a part of it. So the expectation is positive, but of course the media's ability to play that role is restricted in most societies either by political pressure or restricted by economics, and often restricted by the people themselves. What we have seen in recent decades is that what we used to think of as an entirely positive force of people power, it turns out that people power can be anti-democratic, people power can be intolerant and the media that are trying to perform the democratic rule is quite often hemmed in by people power, as well as by government, and by big business.

HYL: Yes. And, now looking at US politics’ influence on the global stage with regard to fake news. A definitional change happened with Trump's mislabelling of mainstream news as fake news, when he infamously called CNN fake news. And then later on, claiming to invent the home on fake news. How does this impact on a global scale — the usage of the term fake news turned around in its whole definition, how does that play on the media and also how society treats this issue?

CG: Well, most of us who study media and report positive and negative sides of the media believe that “fake news” can be a very misleading and unhelpful term, precisely because it's been kind of captured by demagogues like Donald Trump, as well as Rodrigo Duterte in the Philippines and others. It's very important to keep in mind two very separate phenomenon. One is disinformation, these are deliberate attempts to mislead and yes there are media in the world that are engaged in disinformation. They are not trying to tell the truth, they are twisting facts, they are manipulating public opinion, they are a problem. But when the likes of Donald Trump and Rodrigo Duterte use the term “fake news”, that's not really what they're talking about. They're talking about what might be called good-faith media that are in fact, trying to strive for truth, of course naturally getting some things wrong. But the problem that the demagogues have with good faith, professional media organizations is not that they are sometimes guilty of inaccuracy. The problem that they have with these media is that they sometimes correctly, call out bad behaviour on the part of governments, so fake news is a pejorative term that is used to undermine credibility in relatively reliable media... which is of course extremely dangerous and it is dangerous for politicians to use this language to undermine what is really a key democratic institution, which is independent media that are able to speak truth to power, and this is deliberate. We should see the loose use of this term fake news by demagogues as a deliberate strategy to undermine a key democratic institution. It's important to them to spread cynicism in the wider public, to cast doubt on evidence, not just the press, but even universities and experts and scientists and so on. Why do they do this? Demagogues deliberately cast doubt and try to make the general public cynical about all information so that people end up deciding that nobody can be trusted...I'm just going to retreat from public life... everything's relative, everybody has their own truths. And when we have the public retreating in this way, almost paralyzed in this way, who wins? Obviously, who wins are the status quo, right? If people retreat from their responsibilities as citizens, if people are not willing to go through the evidence and decide between right and wrong, you end up with those who are already in power gaining, because they're very difficult to dislodge. And this is precisely why demagogues do this, why they try to cast doubt on reason, that they cause damage on evidence coming from the press, or scientists or universities.

HYL: Do you think this strategy has been successful?

CG: Unfortunately to a frightening degree it has been quite effective in many societies where large numbers of people simply do not know what to believe, and therefore are passive. Pretty large numbers of people are simply misled by disinformation because they are so convinced that the experts who do know what they're talking about, all the media that are trying to strive for truth, are untrustworthy. And this is frightening because in this situation you are creating an open call for bad actors, for politicians who are trying to trample on the rights of vulnerable minorities. Or those who are trying to enable corruption, who are trying to deny the evidence of climate change or pollution. There is a lot of bad stuff going on in the world, precisely because too many people distrust the evidence, and this is not accidental. It's a deliberate ploy by some people in power.

HYL: Who do you think is most vulnerable to the phenomenon of fake news, relating back to the overall idea about disinformation or misinformation?

CG: Do you mean most vulnerable groups or countries?

HYL: it could be countries on the global level, or segments of society.

CG: I think if you look, internationally, there's been some research on which countries are more vulnerable to fake news. What's interesting is that some of these find that a lot has to do with the strength of more credible media. In particular, non-commercial public service broadcasters — public service media like you have in most Western European countries as well as Canada and Australia and so on. There is some research that says that the stronger the public service media, the more resistant the population is to disinformation attempts, because you have reasonably well-funded professional corps of journalists, whose mission is to serve the public interest through journalism. Public service media do this often better than commercial media because they're less distracted by the need to make a profit and strive for ratings or circulation. So there is some evidence of this -- misinformation can be countered if you have a strong well-funded public service media. A concrete example would be the comparison between, say Germany, UK and the US. Germany's election a couple of years ago, was relatively resistant to disinformation compared with, say the UK Brexit referendum – UK having a much more commercial media, despite having the BBC. The US doesn't really have this institution of public service broadcasters.

Within any country, it's a tale as old as time, that those who are most vulnerable to disinformation is going to be the poor and the weak. The working class, the unemployed, ethnic minorities, the marginalized and so on. In any situation, no matter how bad societies get, of course the rich are going to be able to take care of themselves. It’s the poorer segments of society that are disenfranchised, who are going to have their lives disrupted, their futures stolen by something like disinformation. The irony of course is that, populist demagogues like Donald Trump, and many others around the world, claim to be representing the common man, and that's far from the truth. Usually this is just political rhetoric.

The reason why it is the poor and the marginalized who are disadvantaged by this decision is by design. You can think of disinformation as political strategy employed by populist demagogues, by authoritarian, intolerant populists. And populism as a political strategy constructs an “us versus them” dynamic. Populists bring power to themselves by claiming to have identified an enemy of some kind, whether those enemies are immigrants of China on the part of Donald Trump, or Muslims in the case of India and so on. This us-versus-them strategy is extremely powerful because it plays into the followers’ fears of uncertainty, fears of unknown. And it victimizes the targeted group. Much of the most damaging disinformation in the world today is of that kind. It is disinformation-assisted hate propaganda that is spreading conspiracy theories about immigrants and refugees and minorities, for example, so they're quite directly the victims of disinformation, but the poorer segments of society are also indirect victims.

The reason why so many politicians use this technique is precisely because it is simpler to blame a minority group or blame an enemy, rather than actually solve the problems. It is much harder to solve the economic problem of chronic stagflation or declining real wages or chronic unemployment and so on. To do that you actually need to know what you're doing and you need solutions and frankly, these are very, very difficult problems. But it is challenging these problems that will actually improve the lives of real ordinary people. But because it is so difficult to do it, less ethical politicians simply brush this aside and in lieu of solving real problems, claim that the solution is instead to go after some minority or to remove immigrants and so on. So I think this is the bigger reason why disinformation, harms vulnerable segments of society because it is part of a larger political strategy to avoid addressing real problems of social justice in the world.

HYL: Yes, and related to this also is the use of social media, with Twitter, Facebook, being very common grounds for spreading disinformation and misinformation. In the past, four to five years. On one hand it depends where there are strong public service media platforms. Do you think a factor is also where social media is relied upon by certain segments of society for example the elderly, who pass on information that they think is harmless… How do you see the role of social media in this case and how does it interplay with who becomes more vulnerable to fake news being on social media?

CG: I think we'd been learning a lot more about the social media platforms’ methods over the last few years. And what we have learned is clearly quite alarming. I think the fact that misinformation sometimes goes viral on social media, that's the most obvious problem, not necessarily the worst problem. I think we've also got to be careful not to only look at the negatives, because obviously in societies that have more controlled mainstream media environments, which could include many Asian countries, social media is relatively unrestricted. Therefore you can use social media to correct the misinformation that is coming from controlled mainstream media. And this is the situation, perhaps, in most of the world, because most of the world’s population, do not live in liberal democracies where press freedoms is protected. So you need a freer social media to counter the misinformation and propaganda that's coming to you from TV and newspapers and so on.

What is probably more dangerous, though, is the practice of very opaque micro targeting by social media companies, what has been called the business model of surveillance capitalism, whereby the real business that's going on is the accumulation of vast amounts of data about human behaviour in the hands of social media companies that then sell them to customers who want to understand our attitudes and inclinations, in order to influence us in hidden ways, often in ways that we don't even know. This is possibly I think the most significant, most damaging, most anti-democratic aspect of social media because it undermines the whole idea of a marketplace of ideas, and the idea that you become smarter at science and advances that we get to keep an eye on those who govern over us by a free exchange of information. This free exchange of information allows us to then correct what's wrong and in theory, better ideas and better information triumphs. But this type of exchange requires that we know what's going on in the conversation, it has to be an open process. But if I have no idea what information you're getting, I have no way to correct your perceptions and likewise you have no idea what information I'm getting on my social media. I may be told untruths about you, you may be told untruths about me and we will never figure it out.

We won't even know this because in sophisticated micro targeting, who's being targeted with what is something that's completely opaque to the rest of us. So this inability to have an open conversation, I think it's quite devastating for the whole idea of a public sphere in a common space where we as a society can have conversations and clarify each other's misconceptions and correct one another, represent our interests, share our values. So there needs to be this common space and open conversation. And, of course, not everything needs to be in open public space. There is also value in what scholars call a micro public sphere, where we do often want to get together with people who share our values, our culture, because that's where you know we can be ourselves, it's kind of a safe space. But we need to know which is which. In the days before this sort of micro-targeted social media, these were conscious and relatively transparent decisions. We knew what is public, and we knew when we moved into more semi-public areas and private areas and start conversations that way. Right now there's very little understanding, even if we try to understand, there is no way to know if the information that we're getting is public or private. Am I given this information because I'm a Singaporean or because I'm a man or because I’m a Manchester United fan or because of some other thing that I have revealed about myself through social media even without myself knowing. There haven't been a lot of strong calls for increased regulation of social media platforms, at minimum there needs to be far greater transparency. Who's paying for what, what kind of data to social media companies have about the public, these really need to be transparent. I think this can be done without restricting free speech unnecessarily. At the moment, I think the growing consensus that social media platforms are under-regulated.

HYL: Right. So your perspective is that understanding who is paying for the feeds which are coming up on your own page is important. And behind that also is the algorithm - the collecting of data, how they are processed, and then how they feed back the information that they think you should be seeing, from an advertising revenue perspective, or from engagement perspective -- the whole business model of using the information. That’s very interesting. You talk about social media maybe initially being seen as a space for open conversations but actually not really being so, having the business model muddying the way in which we have been engaging. How do you see the role between media and social media in navigating this, who can steer the discourse into a proper conversation, whether is it as a micro public sphere or other, in what sense can this conversation happen?

CG: I think the first thing that we as a society need to do, is to question the assumptions that we have that social media substitutes for media -- media as a means of institutionalized journalism. I don't think it does. I think what we should think of social media as, is an extension of conversations. It’s the social part of it that has been put on steroids with digital technology. So Facebook and Twitter and so on are the 21st century digital equivalent of our conversations. They're not really an evolution of institutional news media. So once we understand that then I hope that we will realize that no matter how many people are on social media, no matter how successful they are, they do not substitute for the role that institutionalized organized journalism plays. In fact, journalism uses social media as one of its outlets, so they're not like-for-like, they're not substitutes for one another.

The danger of course, in many people thinking that now that we've got social media, the health of journalism is not so important, is then we see journalism under resourced in most countries. And there simply is just not enough money going into institutionalized journalism so because the news media organizations haven't found a business model that works in the digital age. And this is a problem. I think regulating social media platforms on the one hand is necessary, but that's not going to solve this problem. This deeper problem of where societies don't really have strong sustainable news media to support democratic life… So much more thought needs to be given to this other problem -- how do we sustain reliable, professional journalism. I hope that people realize that this is something seriously wrong. The whole idea is having professional journalists in the news organizations find out stuff for us and try to inform and educate the rest of us, because quite sensibly more societies in the world have reached a stage where they realize there is no way that an average citizen can keep up with what's going on in their society and what they're supposed to know simply by going out and finding out themselves. Even now in the age of the internet, we simply do not have the time, no matter how smart, how internet savvy we are. It is simply impossible for the vast majority of citizens to, for example, scrutinize what's going on in the legislature, or to find out what this big business is doing, to investigate whether a company is polluting a river or not and so on. There're so many ways in which things going on around us can either kill us, or give us amazing opportunities to improve ourselves and there is no way we can keep in touch with all of this. And this is why, quite sensibly, for centuries societies have delegated the job to a professional class of full-time information seekers who make sense for us.

So the simple question that we ask citizens to contemplate is: since a century ago when the model of professional news media was formed, do you think life has become more complex or less complex? Do you think that there are more things to keep in touch with or less things to keep in touch with? Of course, life has become exponentially more complex than it was. It was tough in the 1920s to keep up with all societies of the world, how much tougher is it now in the 2020s? And isn’t it therefore a huge problem that our capacities to keep in touch with this world has been declining over the last couple of decades? Isn't that a major challenge for human society and for democracy? And I would say even for human existence -- because some of these issues can literally kill us, whether it's pandemics or the climate crisis and so on. It is a matter of survival, that we have the capacity to inform ourselves better, and so much more attention needs to be given to the health of journalism and news media. When that happens, frankly I think the problems that we see in social media today in information will shrink because then we would have reliable information coming to us.

HYL: You touched upon a very interesting point which I want to also relate to, that a lot of news platforms now are doing fact checks, having a dedicated section just for checking facts, which very often come from misquotes, mis-facts from politicians or other key channels. This role is being taken up proactively by certain news channels. Do you think this is a new role, which gives them a certain relevance, with this situation now? Do you see that as being a permanent part of the role of news and of journalism?

CG: The role of independent fact checking whether it's by the news media organizations, or by third party organizations like civic groups and NGOs is certainly welcome… This improved election coverage in say Indonesia and other countries and certainly it's been actively used in the US. I think it helps compensate for the fact that most reporters themselves do not have time to fact check, they don't get this additional help from dedicated fact checkers. So yes, this is a positive thing.

But there's also a dimension that I worry about when it comes to fact checking. I think too many people, including policymakers and the media themselves, seem to believe that this is some kind of magic bullet that will address the problem of disinformation. To be clear, it will not. The reason why it won't, is simply because it is possible to disinform factually. The most sophisticated disinformation campaigns rely only partially on lies. A lot of the most effective disinformation campaigns are primarily made up of distortions that don't need lies. And these are impossible frankly for fact checking to check.

Let me give you a concrete example. In Europe, it would be possible to spread disinformation that refugees and immigrants are causing a crisis because they are sexual predators. This piece of disinformation even has a name called the “rapefugee” crisis in Europe. This can be perpetrated without lies. All you have to do is to set up a website and selectively curate all the articles you can find including articles from factual mainstream media of any kind of sex abuse or sexual harassment case that includes a foreign sounding name as the perpetrator, and you selectively pump this up. Every individual article can be factual. If you are only pushing out articles where the sexually suspected sexual offender has a minority name, this creates a distorted impression that is creating this crisis. This is also done in the US with crime statistics, selectively identifying stories involving Latinos, Asians and so on, who are suspects in crime. Again, each of those stories may be factually correct, but if you are amplifying these stories just by selectivity and pumping them out relentlessly on social media, it creates a false impression.

Another example from Asia is Indonesia’s selectively identifying stories about unscrupulous Chinese businessmen, to suggest that Chinese can’t be trusted, and they control all the wealth in society. In India, selectively highlighting interfaith marriages between Muslim men and Hindu women, to claim the conspiracy theory that there is a “love jihad”, which is one of the most malicious, deadliest conspiracy theories in the world today. The conspiracy theory is basically that Muslims are trying to take over India at the domestic level, that young Muslim men go out to villages, seduce Hindu girls, convert them forcibly to Islam, have lots of babies with them, and this would somehow make Muslims the majority religion in India. So most of the most damaging and dangerous conspiracy theories do not only involve falsehoods. So how in the world do we expect fact checking to help? It will not.

Let’s look at it critically. One reason why there is so much investment into fact checking, is because social media platforms are donating vast sums of money into these efforts. Why are they doing it? They are doing it because it is much better for them to promote the idea that fact checking is the magic bullet. Because it relieves the pressure on them to have their business model regulated. So rather than having scrutiny on their use of surveillance capitalism, they would much rather we focus on this myth that we can solve all these problems with large teams of fact checkers, or even better, if robots are able to stop factual inaccuracies and can shoot them down like snipers. These are complete myths, there is no substitute - on the social media side, to investigating and regulating their business models, and in wider society, we need to look at how hate propaganda works. It does not always use factual inaccuracies.

HYL: Yes, I read this in your book, Hate Spin as well -- the example of love jihad, the consequences that happen can be serious and terrifying.

Now beside fake news, looking at the whole concept of post-truth and how it has crept into politics – what do you think about the term “post-truth” and how does it mean to us, beyond fake news?

CG: I think at its heart, what the term is trying to get at, is the breakdown in the marketplace of ideas that we used to have a lot of faith in. The idea that if we have an open exchange, the better, more reliable truths will emerge through this open contest. But I think the evidence has been mounting that in fact, there is a kind of market failure. That this open exchange does not always work. Sometimes the ideas that triumph are not truthful. Post-truth is a concept that is trying to capture this very troubling development. Here I think we obviously need to ask why is it that so many people are willing to believe untruths, even when it seems there is very persuasive evidence that they should accept as truthful. One possible answer is that they are just dumb. So you have, quite understandably, elites taking condescending attitudes to those who refuse to believe clear evidence. But I think a more productive way to look at it, is to ask why are many people not willing to believe establishment institutions like universities or the press and so on. Obviously there is something deeper going on. I think what’s happened is that vast numbers of people throughout the world just simply feel that the system is not working for them. This is not a post-truth. It is factually accurate that this system is not working for them. The evidence is overwhelming that the system has not worked for them. And I don’t think the timing is coincidental.

The term post-truth emerged over the past ten, fifteen years, which coincided with this period in world economic history where it became quite obvious that the model of capitalist led, profit led, open border and so on, had kind of run its course. It did not result in lifting people out. While there is a class of people who were getting super wealthy, there were also vast numbers of people who were left behind chronically. In the past, there was the American dream – you could tell yourself even though I am of a lower class, my children will have a better life. Increasingly around the world this has evaporated, people realized it is no longer true. The young in many developed economies realized that there is actually no way for them to have a better life than their parents. This is quite a major shift, when you lose hope in the model of progress that has been there for a couple of centuries. And so I think what we have seen is a backlash against the establishment across the board – establishment political parties, also establishment press, establishment universities, establishment science and so on. On that level, maybe people are not that irrational, that they refuse to believe what is coming out of the mouths of these establishment institutions, because the truth is that these institutions have not worked well for them. I see the solution to this post-truth phenomenon is tied to the need to revisit the challenge of achieving social justice, having systems that give dignity to common people and give them hope in a better life.

HYL: As a parting thought, putting yourself in the year of 2021, do you think we should be pessimistic or optimistic about the future? Given what has been building up in society –disenfranchisement, rising inequality, also the need to re-examine the establishments and systems which lead to the rise of post-truth. How do you see it, what is our best hope?

CG: Should we be pessimistic or optimistic? Paradoxically, I think it may be healthier for us to be pessimistic but not without hope. Because if we are optimistic we may think we can continue business as usual, that the system will sort itself out. No, we need to understand the system is not going to sort itself out, by itself. We need people in society to take a stand for things that will help us collectively, whether that’s social justice, or mitigating the climate crisis. We need to take them seriously, and be very pessimistic on what will happen to human society if these things are not done. It is with the sense of realism that we need to start and ask ourselves what can we do to solve the problems. Of course there are enough reasons to be hopeful.

In every society there are individuals and groups trying to do the right thing, to make their societies more just and more sustainable. And we can learn from them. We can make sure that our societies enable these sorts of collective action. We can help promote and sustain media that are part of the solution instead of part of the problem. All these things can be done, but only if we have a realistically and serious view of the challenges we face.

HYL: Thank you very much, Cherian. It has been invaluable to get your insights on this issue and the bigger topics we are very much concerned about -- how do we readjust ourselves, position ourselves to, as they say, build back better. Not just because of Covid, but because of the state of the world as it is today. Thank you very much.

End of Transcript

+ ARTIFACT 05 2020 | Research Paper

Fake News – A Look into the Origins, Developments, and Impact Chow and Lin December 2020

What is “Fake News”?

Origins of the Term Use of the term “fake news” can be traced back to the late 19th century – in publications like Cincinnati Commercial Tribune and The Kearney Daily Hub in 1890, according to Merriam-Webster. There is earlier history of other terms with similar meanings used – “false news” (16th century), “fallax” (1530), “misinformation” (late 16th century), “pseudodoxia” (1646), “taradiddle” (1796).

Definition

From Cambridge Dictionary: False stories that appear to be news, spread on the internet or using other media, usually created to influence political views or as a joke: There is concern about the power of fake news to affect election results.

From Collins Dictionary: If you describe information as fake news, you mean that it is false even though it is being reported as news, for example by the media. False, often sensational, information disseminated under the guise of news reporting “Fake news” was named by Collins Dictionary as Word of the Year in 2017 for being highlighted rampantly and “contributing to the undermining of society's trust in news reporting." (Helen Newstead, Collins Dictionary’s head of language content).

From Dictionary.com: 1) false news stories, often of a sensational nature, created to be widely shared or distributed for the purpose of generating revenue, or promoting or discrediting a public figure, political movement, company, etc.: It’s impossible to avoid clickbait and fake news on social media. 2) A parody that presents current events or other news topics for humorous effect in an obviously satirical imitation of journalism: The website publishes fake news that is hilarious and surprisingly insightful. 3) Sometimes Facetious. (used as a conversational tactic to dispute or discredit information that is perceived as hostile or unflattering): The senator insisted that recent polls forecasting an election loss were just fake news.

From Oxford Dictionary: False reports of events, written and read on websites. Many of us seem unable to distinguish fake news from the verified sort. Fake news creates significant public confusion about current events.

Merriam-Webster has deliberately not included the term in their dictionary because “it is a self-explanatory compound noun — a combination of two distinct words, both well known, which when used in combination yield an easily understood meaning. Fake news is, quite simply, news (“material reported in a newspaper or news periodical or on a newscast”) that is fake (“false, counterfeit”).”

In a paper published in Science journal in March 2018, academic researchers David Lazer and 15 other co-authors defined fake news as "fabricated information that mimics news media content in form but not in organizational process or intent".

Disinformation, Misinformation, Mal-information Researchers and regulators have explained that the term “fake news” is often misused and misunderstood, and that it is important to specify whether it is disinformation, misinformation, or mal-information.

The important differences between disinformation, misinformation and mal-information lie in the intent and basis of the information. From the UNESCO Handbook on “Journalism, Fake News & Disinformation”: Disinformation: Information that is false and deliberately created to harm a person, social group, organisation or country Misinformation: Information that is false but not created with the intention of causing harm Mal-information: Information that is based on reality, used to inflict harm on a person, social group, organisation or country.

For the purpose of this project, our focus is on fake news intentionally spread for political purposes, in the disinformation context. The selection of this is aligned to research and government calls to address the dangers of disinformation, and for the fact that the term “fake news” has been misused for political purposes (elaborated later).

Selected Historical Disinformation Events (Focus on Politics-related)

13th century BCE: Egyptian king Ramses the Great ordered propaganda murals on Egyptian temple walls and a court poem to depict his victory in the Battle of Kadesh. However, the peace treaty signed then with the Hittites revealed that he did not win the battle. 44BC: During the Roman empire, Octavian ran a smear propaganda campaign against Mark Anthony, leading to loss of Anthony’s allies in the senate. 1899-1902: During the Second South African Boer War, many London newspapers painted Boers as being brutal toward Uitlanders and gained support for the British Army in the Boer war. 1920s: In India, Hindu right-wing propaganda campaigns of abductions and conversions of Hindu women by Muslim men resulted in communal clashes in Uttar Pradesh. The “Love Jihad” fake claim has been recurring through 2009 till now. 1939-1945: Nazi regime shut down oppositional newspapers and promoted antisemitic propaganda through its press. Nazi press accounted for over 80% of newspapers circulated in Germany by 1941. 1947-1991: CIA organized political anti Russia Communist propaganda campaigns on US TV networks, radio stations and newspapers, and also set up a broadcasting station targeting Eastern European audience. 1980s: South African apartheid security police ran disinformation campaigns to discredit the African National Congress, including running articles in South African and international newspapers. 2003: New York Times published articles on weapons of mass destruction in Iraq based on accounts of Iraqi defectors; the paper later issued an apology that reflected certain coverage should have been more rigorous to re-examine claims 2015-16: In Philippines, political operations organized networked disinformation campaigns leading up to the presidential elections. 2016: Russia reportedly paid for creation and spreading of fake anti-Hillary Clinton news during the US Presidential elections. Russia’s disinformation “playbook” is reported to be later adopted by other countries including Iran, Venezuela and China. 2016-17: PR agency Bell Pottinger ran a large scale fake news propaganda campaign in South Africa on social media and news outlets targeting race relations 2017-18: Myanmar Rohingya crisis investigations revealed that the military ran anti-Rohingya hate speech campaigns using Facebook 2018: The Brazilian elections saw viral WhatsApp messages mostly favouring Jair Bolsonaro with falsehoods such as election process conspiracies. 2019: Election-related riots break out in Indonesia upon disinformation on social media about the election being stolen and playing up of anti-Chinese sentiments.

Recent Developments in Usage / Misuse of the Term “Fake News”

Reference to social media misinformation Recent popular use of the term “fake news” in the past few years especially in US media has been attributed to Craig Silverman. Silverman was doing a research project for Columbia University’s Tow Center for Digital Journalism in 2014 on the online spread of misinformation, and wrote a section in his research paper about fake news. He publicly used the term in a tweet in October 2014. His use of the term was to describe articles written in journalistic style on sites looking like real news websites, which were able to achieve high volume of sharing and engagement on social media networks like Twitter and Facebook.

The use of the term in the public sphere rose with the 2016 US elections. In November 2016, Silverman published an article on Buzzfeed about 140 US politics websites with American-sounding domain names being run from a Macedonian town Veles. On 9 December 2016, after the “Pizzagate shooting incident”, Hillary Clinton mentioned in a public speech, “the epidemic of malicious fake news and false propaganda that flooded social media over the past year."

Labelling of media

In January 2017, Donald Trump called CNN “fake news”, after it reported on a dossier alleging Trump’s ties to Russia. This has been seen as a definitional shift for the term. In October 2017, Donald Trump claimed in an interview that he invented the word “fake” or the term “fake news”, referring to US media. He has used the term on multiple occasions to criticise the credibility of news outlets. On January 17, 2018, Trump released the 2017 Fake News Awards, citing that “over 90% of the media’s coverage of President Trump is negative”. The list comprised reporting by New York Times, ABC News, CNN, Time, Washington Post and Newsweek.

In a similar move, Philippines President Rodrigo Duterte called news network Rappler a “fake news outlet” at a press conference on January 16, 2018, in response to an article published about Special Assistant to the President, Bong Go.

Google search trends

Google Trends analysis shows that since January 2016, google searches for “fake news” peaked during these periods: November 18 2016 (Silverman’s Buzzfeed News article on Macedonia website creators) – this was the first peak; December 9 2016 (Hillary Clinton’s speech after Pizzagate); January 11 2017 (Trump’s press conference labelling CNN); January 18 2018 (Donald Trump’s Fake News Award); October 8-10 2018 (Bolsonaro’s win of first round of Brazilian elections being reported to be linked to fake news); March 14-24 2020 (news on Covid-19 disinformation on various topics including ibuprofen usage, protection methods attributed to Brazil Oswaldo Cruz Foundation, Ambev suspension of production in Brazil) – this was the highest of these peaks

Source: Google Trends

Recent Development Drivers

Post-truth Phenomenon The recent rise and use of fake news and disinformation has been linked to “post-truth” politics and public sentiment. Post-truth, according to Oxford Dictionary, is defined as ‘relating to or denoting circumstances in which objective facts are less influential in shaping public opinion than appeals to emotion and personal belief’. “Post-truth” was named Oxford Dictionary as its Word of the Year in 2016 following increased usage during UK’s Brexit referendum and US presidential elections. Post-truth arguably has been impacted by postmodern relativism which rose in late 20th century. The post-truth phenomenon has been gaining traction on the back of rising societal divisions and economic inequality, anti-elitism sentiment and linked to political campaign propaganda.

Social Media

The rapid development of social media in the early 2000s came after that of the Internet and the World Wide Web in 1990s. Facebook had 2.60 billion monthly active users as of March 31, 2020 and is the largest social media platform, followed by YouTube and Whatsapp. The large global social platforms, notably Facebook, Twitter and Whatsapp have been called out for being channels for dissemination of fake news. In a study about the activity of “untrustworthy websites” during 2016 US election, it was found that Facebook was by far the site most visited by people prior to visiting a fake news website. According to BuzzFeed News, the top 50 most viral false stories on Facebook in 2018 generated 22 million shares, reactions and comments.

The role of Facebook in facilitating the spread of fake news is compounded by the collection and usage of user data. Microtargeting techniques deployed in its business model that seeks to optimize user engagement and increase advertising revenue are criticised to create echo chambers. The Facebook-Cambridge Analytica data scandal which broke out in 2018 revealed that as many as 87 million Facebook users’ information was obtained to develop psychological profiles of US voters. A study on opt-in user data from 2012 to 2016 from 200,000 users on Facebook, Reddit, Twitter and online news sites found that while “all three social media sites connect their users to a more diverse range of news sources than they would otherwise visit”, “Facebook tends to polarize users, particularly conservative users, more than other social media platforms.”

How users choose to share news has also been found to be a key factor. A study on 126,000 English news stories on Twitter data during 2006 to 2017 found that false news stories are 70% more like to be retweeted than true ones. Also, news about politics and urban legends spread the fastest and were most viral. The researchers suggested that the underlying reason for these results could be inclination for people to share “novel” news to gain attention.

Societal Impact of Disinformation

The impact of disinformation can be classified into these main areas: Spread of disinformation Attitude change or reinforcement Behavioural change and actions Societal impact

Examples of societal impact of disinformation include:

Change in political trust and political behavior The 2018 study by Ognyanova et. al. found that fake news exposure was related to stronger political trust by moderate-to-conservative respondents but lower political trust among liberals – thus it strengthened status quo governmental institutions among existing supporters. A 2020 study by Andrew M. Guess et. al. which did controlled experiments where some respondents were shown a news article from untrustworthy websites however found the one-off consumption of news from untrustworthy sites did not have measurable effect on their feelings about political parties and media. A 2018 European Commission High Level Group of Experts Report on fake news and online disinformation emphasize the threat of disinformation being used to undermine the integrity of elections. Tactics would include disinformation about voting information, rumours on unfair voting practices and non-transparent political advertisements.

Harmful behaviour during COVID-19 pandemic due to “infodemic” – global spread of misinformation that causes public health crisis A May 2020 study looking at US, UK, Netherlands and Germany found that people with stronger disinformation perceptions were less willing to comply with official guidelines and also actively avoided news on the pandemic. In UK, in March and April 2020, 5G telecommunications masts were vandalized or destroyed by groups of people who believed that they spread the virus. This untruth was brought up on a Belgian television interview and was spread online through Facebook groups, Russia Today and conspiracist website Infowars. A June 2020 study in Canada found that people with misperceptions of COVID-19 had viewed the virus as less risky and had lower compliance with social distancing measures. Misperceptions had a greater effect on social distancing than the level of social media exposure. A November 2020 study in US on the forms of COVID-19 misinformation found though that conspiracy theories were more widely believed than medical misinformation (e.g. use of UV light, disinfectants, hydroxychloroquine).

Decline in trust of mainstream news agencies

A 2018 study (Ognyanova et. al.) done just before and after the US mid-term elections found that fake news exposure was associated with a decline in trust of the mainstream media. This could be due to discrediting of mainstream media by fake news, and the existence of misinformation made to seem like proper journalism that confuses and diminishes real news credibility. A decline of trust in the media in turn has other societal implications. A 2018 Pew Center study on US members of public ability to distinguish between factual and opinion statements found that those with lower level of trust in national news organizations were less likely able to distinguish fact from opinion.

References

Dictionary.com. Definition of “fake news”. In dictionary.com [online]. https://www.dictionary.com/browse/fake-news?s=t Cambridge Dictionary. Definition of “fake news”. In Cambridge Dictionary [online]. https://dictionary.cambridge.org/us/dictionary/english/fake-news Oxford Dictionary. Definition of “fake news”. In Oxford Dictionary [online]. https://www.oxfordlearnersdictionaries.com/definition/english/fake-news?q=fake+news Collins Dictionary. Definition of “fake news”. In Collins Dictionary [online]. https://www.collinsdictionary.com/us/dictionary/english/fake-news Lazer, David M. J. et. al. The Science of Fake News. 2018. In Science journal [online]. https://science.sciencemag.org/content/359/6380/1094 The Real Story of ‘Fake News’. In Merriam-Webster [online]. https://www.merriam-webster.com/words-at-play/the-real-story-of-fake-news Poole, Steven. 2019. Before Trump: the real history of fake news. In The Guardian [online]. https://www.theguardian.com/books/2019/nov/22/factitious-taradiddle-dictionary-real-history-fake-news Posetti, Julie and Matthews, Alice. A short guide to the history of ‘fake news’ and disinformation. 2018. In International Center for Journalists [online]. https://www.icfj.org/sites/default/files/2018-07/A%20Short%20Guide%20to%20History%20of%20Fake%20News%20and%20Disinformation_ICFJ%20Final.pdf Rattini, Kristin Baird. Who was Ramses II? 2019. In National Geographic [online]. https://www.nationalgeographic.com/culture/people/reference/ramses-ii/ MacDonald, Eve. The fake news that sealed the fate of Antony and Cleopatra. 2017. In The Conversation [online] https://theconversation.com/the-fake-news-that-sealed-the-fate-of-antony-and-cleopatra-71287 Kent, Kelley S. Propaganda, Public Opinion, and the Second South African Boer War. 2013. In Inquiries Journal [online]. http://www.inquiriesjournal.com/articles/781/propaganda-public-opinion-and-the-second-south-african-boer-war United States Holocaust Memorial Museum. Writing the News. In Holocaust Encyclopedia. https://encyclopedia.ushmm.org/content/en/article/writing-the-newss Osgood, Kenneth. The C.I.A.’s Fake News Campaign. 2017. In New York Times [online]. https://www.nytimes.com/2017/10/13/opinion/cia-fake-news-russia.html New York Times Editors. From the Editors; The Times and Iraq. 2004. In New York Times [online]. https://www.nytimes.com/2004/05/26/world/from-the-editors-the-times-and-iraq.html Gupta, Charu. Hindu Women, Muslim Men: Love Jihad and Conversions. 2009. In Economic and Politics Weekly Journal. https://www.academia.edu/2185122/Charu_Gupta_Hindu_Women_Muslim_Men_Love_Jihad_and_Conversions_Economic_and_Pollitical_Weekly_44_51_2009_13_15 South Africa Press Association. Stratcom Used Winnie to Discredit ANC: McPherson. 1997. In Department of Justice and Constitutional Development Republic of South Africa [online]. https://www.justice.gov.za/trc/media/1997/9711/s971128n.htm African Network of Centers for Investigative Reporting. The Guptas, Bell Pottinger and the fake news propaganda machine. 2017. In Times Live. https://www.timeslive.co.za/news/south-africa/2017-09-04-the-guptas-bell-pottinger-and-the-fake-news-propaganda-machine/ Newman, Melanie, et.al. Bell Pottinger “Incited Racial Hatred” in South Africa. 2017. IN The Bureau of Investigative Journalism [online]. https://www.thebureauinvestigates.com/stories/2017-09-05/for-whom-the-bell-pottinger-tolls-1 Ong, Jonathan Corpus and Cabanes, Jason Vincent A. Architects of Networked Disinformation. 2018. In Newton Tech4Dev Network [online]. http://newtontechfordev.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/02/Architects-of-Networked-Disinformation-Executive-Summary-Final.pdf Vasu, Norman et. al. Fake News: National Security in the Post-truth Era. 2018. In Nanyang Technological University S. Rajaratnam School of International Studies website [online]. https://www.rsis.edu.sg/wp-content/uploads/2018/01/PR180313_Fake-News_WEB.pdf United Nations Human Rights Council. Myanmar: UN Fact-Finding Mission releases its full account of massive violations by military in Rakhine, Kachin and Shan States. 2018. In UNHRC [online]. https://www.ohchr.org/EN/HRBodies/HRC/Pages/NewsDetail.aspx?NewsID=23575&LangID=E Mozur, Paul. A Genocide Incited on Facebook, With Posts From Myanmar’s Military. 2018. In New York Times [online]. https://www.nytimes.com/2018/10/15/technology/myanmar-facebook-genocide.html Frenkel, Sheera et. al. Russia’s Playbook for Social Media Disinformation Has Gone Global. 2019. In New York Times [online]. https://www.nytimes.com/2019/01/31/technology/twitter-disinformation-united-states-russia.html Conger, Kate. Twitter Removes Chinese Disinformation Campaign. 2020. In New York Times [online]. https://www.nytimes.com/2020/06/11/technology/twitter-chinese-misinformation.html Temby, Quinton. Disinformation, Violence, and Anti-Chinese Sentiment in Indonesia’s 2019 Elections. 2019. In ISEAS [online]. https://www.iseas.edu.sg/images/pdf/ISEAS_Perspective_2019_67.pdf Avelar, Daniel. WhatsApp fake news during Brazil election ‘favoured Bolsonaro’. 2019. In The Guardian [online]. https://www.theguardian.com/world/2019/oct/30/whatsapp-fake-news-brazil-election-favoured-jair-bolsonaro-analysis-suggests Jacoby, James. 2018. Frontline Interview – The Facebook Dilemma – Craig Silverman. In PBS [online]. https://www.pbs.org/wgbh/frontline/interview/craig-silverman/ Wendling, Mike. 2018. The (almost) complete history of ‘fake news’. In BBC News [online]. https://www.bbc.com/news/blogs-trending-42724320 Schaub, Michael. 2017. Trump’s claim to have come up with the term ‘fake news’ is fake news, Merriam-Webster dictionary says. In Los Angeles Times [online]. https://www.latimes.com/books/jacketcopy/la-et-jc-fake-news-20171009-story.html Silverman, Craig. I Helped Popularize The Term “Fake News” and Now I Cringe Every Time I hear It. 2017. In Buzzfeed News [online]. https://www.buzzfeednews.com/article/craigsilverman/i-helped-popularize-the-term-fake-news-and-now-i-cringe Hudson, Jerome. How Buzzfeed Editor Craig Silverman Helped Generate the Fake News Crisis. 2016. In Breitbart [online]. https://www.breitbart.com/the-media/2016/12/20/how-buzzfeed-editor-craig-silverman-helped-generate-the-fake-news-crisis/ Petty, Martin and Lema, Karen. Philippines' Duterte blasts news site Rappler, but denies stifling media. 2018. In Reuters [online]. https://www.reuters.com/article/us-philippines-media/philippines-duterte-blasts-news-site-rappler-but-denies-stifling-media-idUSKBN1F50HL Silverman, Craig and Alexander, Lawrence. How Macedonia became a global hub for pro-Trump misinformation. 2016. In Buzzfeed News [online]. https://www.buzzfeednews.com/article/craigsilverman/how-macedonia-became-a-global-hub-for-pro-trump-misinfo#.gabryb1QZM Zengerle, Patricia. Clinton calls 'fake news' a threat to U.S. democracy. 2016. In Reuters [online]. https://fr.reuters.com/article/us-usa-clinton-fakenews-idUSKBN13X2R6 Google Trends Analysis of “Fake News”. Accessed December 3, 2020. Google Trends [online]. https://trends.google.com/trends/explore?q=fake%20news BBC. What is 2017’s word of the year? 2017. In BBC News [online]. https://www.bbc.com/news/uk-41838386 Team GOP. The Highly-Anticipated 2017 Fake News Awards. 2018. In GOP.com [online]. https://gop.com/the-highly-anticipated-2017-fake-news-awards/ BBC Reality Check team and BBC Monitoring. Coronavirus and ibuprofen: Separating fact from fiction. 2020. In BBC News [online]. https://www.bbc.com/news/51929628 Fiocruz. Fiocruz clarifies false information. 2020. In Fiocruz [online]. https://portal.fiocruz.br/noticia/fiocruz-esclarece-informacoes-falsas Jornal Beira-Rio. Ambev’s Note on Production Suspension is Just Fake News. 2020. In Jornal Beira-Rio [online]. http://jornalbeirario.com.br/portal/?p=67848 Oxford University Press. Word of the Year 2016. 2016. In Oxford Languages [online]. https://languages.oup.com/word-of-the-year/2016/ Gooch, Anthony. Bridging divides in a post-truth world. 2017. In OECD [online]. http://www.oecd.org/digital/bridging-divides-in-a-post-truth-world.htm Fukuyama, Francis. 2017. The Emergence of a Post-Fact World. In Project Syndicate [online]. https://www.project-syndicate.org/onpoint/the-emergence-of-a-post-fact-world-by-francis-fukuyama-2017-01 Facebook. Facebook Reports First Quarter 2020 Results. 2020. In Facebook [online]. https://investor.fb.com/investor-news/press-release-details/2020/Facebook-Reports-First-Quarter-2020-Results/default.aspx Silverman, Craig and Pham, Scott. These are 50 of the biggest fake news hits on Facebook in 2018. In Buzzfeed News [online]. https://www.buzzfeednews.com/article/craigsilverman/facebook-fake-news-hits-2018 Guess, Andrew M., Nyhan, Bredan, and Reifler, Jason. Exposure to untrustworthy websites in the 2016 U.S. election. 2018. In Dartmouth University. https://www.dartmouth.edu/~nyhan/fake-news-2016.pdf Confessore, Nicholas. Cambridge Analytica and Facebook: The Scandal and the Fallout So Far. 2018. In New York Times [online]. https://www.nytimes.com/2018/04/04/us/politics/cambridge-analytica-scandal-fallout.html Lapowsky, Issie. How Cambridge Analytica Sparked the Great Privacy Awakening. 2019. In Wired [online]. https://www.wired.com/story/cambridge-analytica-facebook-privacy-awakening/ Newman, Caroline. Study: How Facebook pushes users, especially conservative users, into echo chambers. 2020. In University of Virginia [online]. https://news.virginia.edu/content/study-how-facebook-pushes-users-especially-conservative-users-echo-chambers Meyer, Robinson. The Grim Conclusions of the Largest-Ever Study of Fake News. 2018. In The Atlantic [online]. https://www.theatlantic.com/technology/archive/2018/03/largest-study-ever-fake-news-mit-twitter/555104/ Vosoughi, Souroush, Roy, Deb, and Aral, Sinan. The Spread of True and False News Online. 2018. In MIT Initiative on the Digital Economy Research Brief [online]. http://ide.mit.edu/sites/default/files/publications/2017%20IDE%20Research%20Brief%20False%20News.pdf University of California Santa Barbara Center for Information Technology & Society. Fake news. In UCSB CITS [online]. https://www.cits.ucsb.edu/fake-news/danger-social Ognyanova, Katerine et.al. Misinformation in action: fake news exposure is linked to lower trust in media, higher trust in government when your side is in power. 2020. In Misinformation Review [online]. https://misinforeview.hks.harvard.edu/article/misinformation-in-action-fake-news-exposure-is-linked-to-lower-trust-in-media-higher-trust-in-government-when-your-side-is-in-power/ West, Darrell M. Brookings survey finds 57 percent say they have seen fake news during 2018 elections and 19 percent believe it has influenced their vote. 2018. In Brookings [online]. https://www.brookings.edu/blog/techtank/2018/10/23/brookings-survey-finds-57-percent-say-they-have-seen-fake-news-during-2018-elections-and-19-percent-believe-it-has-influenced-their-vote/ Hameleers, Michael et. al. Feeling “disinformed” lowers compliance with COVID-19 guidelines: evidence from the US, UK, Netherlands and Germany. 2020. In Harvard Kennedy School Misinformation Review [online]. https://misinforeview.hks.harvard.edu/article/feeling-disinformed-lowers-compliance-with-covid-19-guidelines-evidence-from-the-us-uk-netherlands-and-germany/ Colley, Thomas, et.al. Disinformation’s Societal Impact: Britain, Covid, And Beyond. 2020. In Defence Strategic Communications [online]. https://www.stratcomcoe.org/tcolley-fgranelli-and-jalthuis-disinformations-societal-impact-britain-covid-and-beyond Bridgman, Aengus, et. al. The causes and consequences of COVID-19 misperceptions: understanding the role of news and social media. 2020. In Harvard Kennedy School Misinformation Review [online]. https://misinforeview.hks.harvard.edu/article/the-causes-and-consequences-of-covid-19-misperceptions-understanding-the-role-of-news-and-social-media/ Enders, Adam M., et.al. The different forms of COVID-19 misinformation and their consequences. 2020. In Harvard Kennedy School Misinformation Review [online]. https://misinforeview.hks.harvard.edu/article/the-different-forms-of-covid-19-misinformation-and-their-consequences/ Guess, Andrew M., et. al. “Fake news” may have limited effects beyond increasing beliefs in false claims. 2020. In Harvard Kennedy School Misinformation Review [online]. https://misinforeview.hks.harvard.edu/article/fake-news-limited-effects-on-political-participation/ EC High Level Group of Experts on Fake News and Online Disinformation. Final report of the High Level Expert Group on Fake News and Online Disinformation. 2018. In European Commission [online]. https://ec.europa.eu/digital-single-market/en/news/final-report-high-level-expert-group-fake-news-and-online-disinformation Mitchell, Amy, et. al. Distinguishing Between Factual and Opinion Statements in the News. 2018. In Pew Research Center [online]. https://www.journalism.org/2018/06/18/distinguishing-between-factual-and-opinion-statements-in-the-news/