I’m Worth My Bread

2025

I’m Worth My Bread examines dynamic systems of value creation and exchange within national and global comparative frameworks. A selection of locally consumed food products embody the progression of invention, industry and culture through history and the present.

The food items form a total purchase value equivalent to the per capita per-day rate of a country’s Gross Domestic Product (GDP) -- a metric developed by Simon Kuznets in the 1930s to assess national economic health against the backdrop of the Great Depression. By definition, GDP measures the monetary value of final goods and services produced in a country within a given period of time. Recognition of its limitations have led to complementary metrics and accounting of externalities, and it remains a common headline indicator internationally.

The project title references a letter written by Vincent van Gogh to his brother Theo in 1882, considering individual and relational parameters through societal lenses of the time. The landscape of interlocking constituents and spaces overlay notions of functionality, associated attributes, identity and values.

This project started with an initial focus on Singapore on the 60th year of its independence, peering into its historical journey and aspirational future. The small island state’s development has been anchored in value-added economic activities which enable high GDP per capita to be achieved. In 2023, Singapore was ranked top globally in GDP per capita, PPP (purchasing power parity)(current international dollars).

An examination of iconic food products in Singapore through different eras engages with daily consumption behavior, as well as underlying commercial structure and industrial technology. Milo powder and Toblerone chocolate were amongst imported food products in 1965, reflecting Singapore’s trading networks and post-colonial post-war influences. Campbell’s condensed soup and Nescafe instant coffee powder leverage on canning and dehydration processes to offer consumers convenience and price efficiency. The stories of home-grown brands such as Ayam Brand, Khong Guan, Prima Taste and DoDo intertwine with Singapore’s passage of connectivity, import substitution, safety and security, heritage commercialization, productivity, innovation and premiumization; an evolution of relevance and competitiveness amidst regional and global market changes. The items were bought off the shelves of Cold Storage and NTUC Fairprice, respectively the oldest and largest supermarket chains in Singapore. Deconstructed from their brand elements, these objects invite observation, inference and enquiry.

This exhibited case study was undertaken in Singapore in 2025. Using latest figures then, the GDP per capita of Singapore per day was SGD 332 (USD 245) in 2024, each frame representing a SGD 10 denomination.

Installation View: I’m Worth My Bread

2025 | Artist’s Proof: Singapore at 60, Presented by The Culture Story.

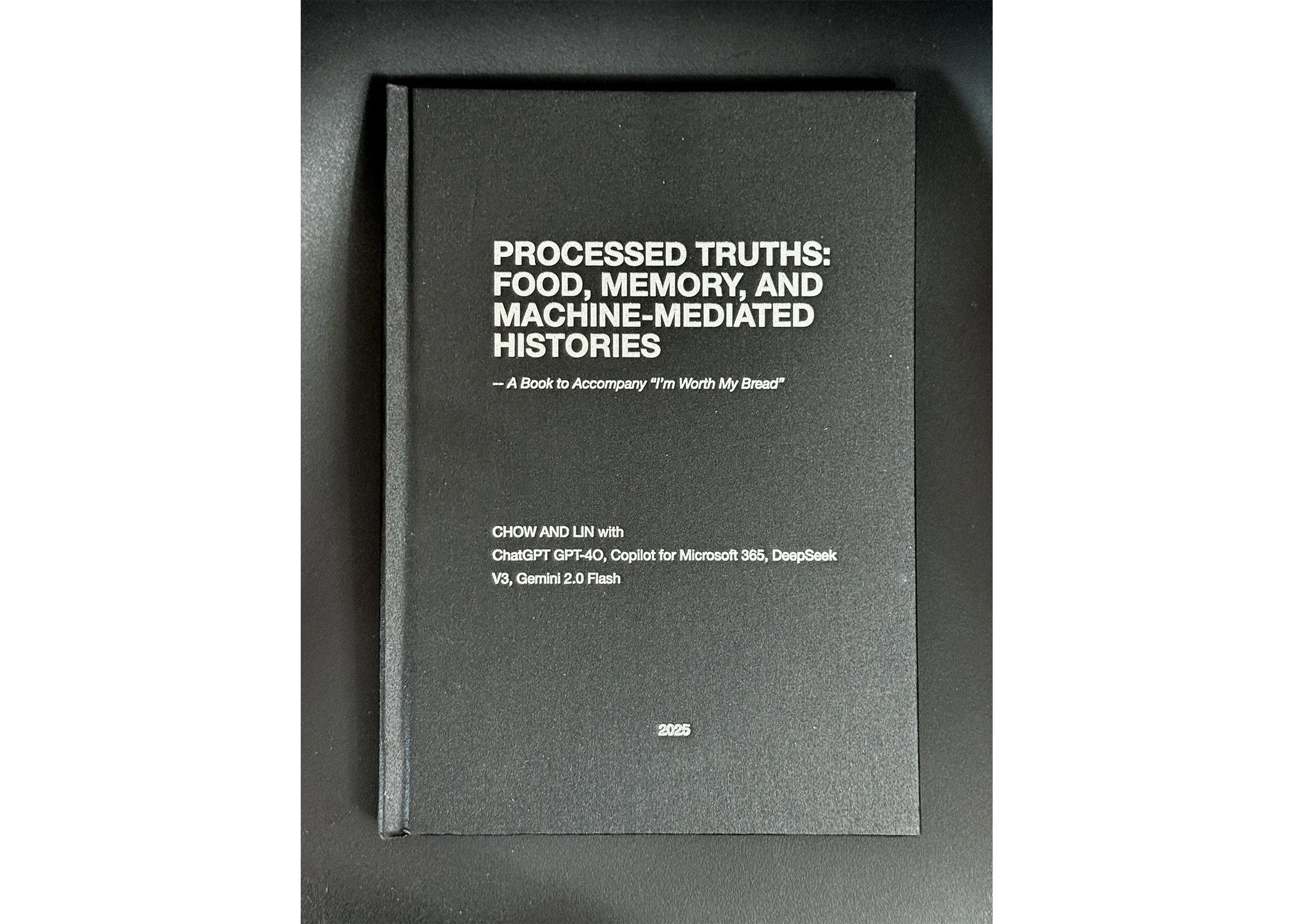

Installation View: Processed Truths: Food, Memory, and Machine-Mediated Histories. A book to accompany “I’m Worth My Bread”

2025 | CHOW AND LIN with ChatGPT GPT-4.0, Copilot for Microsoft 365, DeepSeek V3, Gemini 2.0 Flash

“……………..The invention of food canning in the early 19th century stands as a monumental achievement, a seemingly simple yet profoundly impactful innovation that continues to resonate through the fabric of our global food system. Born from the exigencies of wartime preservation, this ingenious method of sealing and sterilizing food within durable containers rapidly transcended its initial military applications, blossoming into a transformative force that fundamentally reshaped the food industry, intricately wove complex global supply chains, and indelibly marked the culinary landscapes of diverse cultures. From the pioneering efforts of Nicolas Appert and the crucial adaptation to metal cans by Peter Durand, the journey of canning is a testament to human ingenuity in addressing the fundamental need for reliable food preservation.

The subsequent industrialization of canning during the 19th and 20th centuries catalyzed a revolution in food production and distribution. Mechanized can manufacturing, coupled with a growing scientific understanding of food spoilage, enabled the mass production of affordable and shelf-stable food products. This not only addressed issues of seasonal availability and geographical limitations but also fostered the rise of major food corporations and the development of specialized agricultural and fishing industries. The ability to transport and trade canned goods across vast distances laid the groundwork for the intricate international supply networks that define our modern global economy, connecting regions of abundance with areas of demand.

In conclusion, the unassuming tin can, conceived out of a practical necessity for preservation, has etched an indelible mark on the trajectory of human civilization. Its multifaceted impact on the food industry, the intricate architecture of global supply chains, and the diverse tapestry of food cultures is undeniable and far-reaching. As we navigate the complexities of feeding a growing global population while striving for more sustainable and nutritious food systems, the foundational principles of food canning, coupled with cutting-edge research and development, will undoubtedly continue to play a vital role in shaping the future of how we produce, distribute, and ultimately, consume our sustenance.”

Excerpt from the book, “Processed Truths: Food, Memory, and Machine-Mediated Histories”, written by Chow and Lin with ChatGPT GPT-40, Copilot for Microsoft 365, Deepseek V3, Gemini 2.0 Flash

This is an 168-page book accompaniment to the art project by Chow and Lin – “I’m Worth My Bread” - Singapore 2025 case study. This book is co-written by Chow and Lin with Artificial Intelligence (AI) Large Language Model (LLM) tools. The intent is to understand the potential uses and limitations of such tools, consider the evolving structure of information, and question the role of voice, agency and intent in artistic research.

-

I. INTRODUCTION

This is an accompaniment to the art project by Chow and Lin – “I’m Worth My Bread” - Singapore 2025 case study. This book is co-written by Chow and Lin with Artificial Intelligence (AI) Large Language Model (LLM) tools. The intent is to understand the potential uses and limitations of such tools, consider the evolving structure of information, and question the role of voice, agency and intent in artistic research.

This book comprises three main sections. First, an explanation of the methodology used in producing the texts. Second, descriptions of commercial brands related to the art work. Third, essays on topics which explore underlying issues of interest.

A. Methodology and Disclaimer

The write-ups and essays have been derived using open (AI) AI LM tools with manual prompts and comparative techniques. Four AI tools were used, namely:

ChatGPT GPT-4o

Copilot for Microsoft 365

DeepSeek V3

Gemini 2.0 Flash

With the current platforms’ algorithms and databases, there may be informational inaccuracies and inferences. Thus they need to be cross-checked before usage. The intention of this process is to enable understanding of the possibilities and limitations of using AI tools for such research.

B. Process

The overall process taken to produce the texts for brand descriptions and essays are as follows.

Using all four platforms, prompt for a first draft

For brand descriptions: “Write a 150-word summary about Coca-Cola (beverage brand), in a tone that is critical, artistic and formal with interesting facts covering its brand and corporate development, key products, inventions or innovations, controversies and challenges. Make sure the facts are correct, using credible sources.”

For essays: “Write a 5000-word essay on the following topic. Write in an academic style -- complete sentences and paragraphs, in-depth analysis, with proper citation list (MLA style). Use sources from the internet. Topic: Singapore, a 60-Year-Old Nation State. An assessment of Singapore in 2025, that considers its history, development, uniqueness, relevance in the current global landscape and possible future journey.”

Compare the texts generated; triangulate. Be alert about differences in what should be objective facts e.g. founding year. Prompt to ask about these “facts”. The platform/s should then reply with a source, or to say that the statement was inaccurate, and explain what it should actually be. For the latter, prompt to revise to the accurate fact. The “smell” test is as important (or even more) here, as when using search engines.

Example from GPT-4o: “I was unable to verify the exact year 1973 for the introduction of Mitsuya Tasty Stick in Singapore from external sources. This date might have been inferred or approximated. To provide accurate and reliable information, further confirmation from the official Calbee or other credible sources would be necessary. Would you like me to adjust the summary accordingly or check for another reliable source to validate this?”

Example from DeepSeek: “Based on the search results provided, there is no evidence to support the claim that Ayam Brand was acquired by Denis Group.”

Example from Gemini on Glory Food: “I apologize for the earlier inaccuracies regarding Glory Food's involvement in food safety and labeling concerns. After thorough research, I have found no credible sources indicating that Glory Food faced such issues in 2021. If you have any other questions or need further assistance, please feel free to ask.”

Prompt “Fact check this”.

Gemini’s fact checking would say: The summary is largely accurate, but here's a detailed fact check with some nuances, and follow on to say what are the strengths, points for consideration, credible sources for fact checking.”

DeepSeek would explain the verification based on provided search results, conclude about which claims have credible evidence, and recommend which sources to cross-check with.

Example from DeepSeek on NTUC Fairprice: “Yes, NTUC FairPrice has expanded into China, though details of its operational scope remain limited in publicly available sources. According to a Q&A platform, the Singapore-based supermarket chain is described as "the largest grocery chain in Asia," with presence in China alongside Singapore and other countries 10. This assertion aligns with the brand’s strategic ambitions, as hinted in earlier corporate narratives about regional growth beyond Southeast Asia…. However, the search results provide no specifics on store formats, locations, or timelines for its Chinese ventures.”

If the terms used sound like they are taken from a corporate press release e.g. “cherished by households”, prompt to remove marketing / PR language.

Prompt “How many words is this”. The answer was almost always not accurate; they would claim it is 150 or 5000 words when it is not. I would copy-paste onto Word, use Word to count, calculate the difference from the word count needed, and prompt it to add / reduce exactly by X number of words, and let me know which words have been added or deleted. Even then, their counting was often not accurate, it seems that they used rough estimation methods and may sometimes include punctuation. I would reiterate process of copy-paste onto Word, use Word to count, prompt AI platform to add / delete words until the desired count is achieved.

Example from Gemini: “I deleted the following five words: "in production, and alleged”.”

Prompt to rewrite after making a few edits, with specific instructions on structure if needed.

C. Observations

It is important to understand the advantages and gaps in using AI LLMs, so as to devise and adjust appropriate methods of use to suit the project objectives. Overall observations are as follows:

AI LLMs work at high speed to generate texts as prompted. For example, it took GPT-4o 51 seconds to generate a 791-word first draft on the topic of “Food history and cultural research using AI” and a MLA-style citation list. Accuracy however is not to be assumed even if the tone seems authoritative (see points further below on AI hallucations and word count).

Systems are trained on certain thinking processes. Prompting is an iterative action, to refine based on examining the text generated.

The systems require specific prompts in straightforward English, covering the content, tone and length if there are any such preferences.

The tools are set up to produce answers or justifications. Especially if the question is asked is topical rather than in a direct fact-check / yes-no manner, prompts would generally result in elaborative responses.

DeepSeek verbalizes (in text) and times its thinking process, which is fascinating to observe and understand. This is useful especially for reasoning problems.

AI hallucinations, misinterpretations of facts are common, thus the importance of tactics such as triangulation and source-checking.

Example from DeepSeek: Stated that Kellogg’s brand was related to Guanghua-Kellogg Executive MBA Program.

Example from GPT-4o on Twisties: “I apologize for the earlier inaccuracy. After further research, I found no credible sources confirming that Twisties products were pulled from Malaysian shelves in 2014 due to halal certification issues. This claim appears to be unfounded. If you would like, I can help revise the summary to remove this point and ensure it accurately reflects the brand's history.”

Similar to the echo chamber effect, information which is widely publicized may be prioritized, whereas non or less public information is neglected. For example, the urban myth about Coca-Cola’s inappropriate Chinese name (蝌蝌啃蜡) when it first entered China, which was earlier widely spread but also disputed. Users need to be conscious that the role of the AI platform is not to be an arbiter of truth or facts, but a synthesizer and extender of information based on its algorithm and training data which has its inherent biases including time period, geographic and language coverage.

Answers generated are non-replicable though sometimes some platforms do give similar answers for certain questions, possibly where based on its training data there may be less ambiguity of answers.

Doing an accurate word count is surprisingly difficult for all the platforms.

Gemini: “You are absolutely correct. I apologize for that. I am still under development, and accurately estimating word count can be challenging.”

All the platforms put disclaimers on veracity. If AI-generated content is not fully checked, disclaimers are necessary.

DeepSeek: “AI-generated, for reference only”

Gemini: “Gemini can make mistakes, so double-check it”

Copilot: “Copilot may make mistakes. Your conversations are personalized and help train AI.”

GPT-4o: “ChatGPT can make mistakes. Check important info.”

DeepSeek tends to often use Chinese sources including Netease, Aliyun, Sohu, Baike. Overall, amongst the tools, DeepSeek tends to have more hallucinations, sometimes mistakes the company, and has less comprehensive coverage of English sources especially western news. For the other platforms, their training data seems focused on English sources.

Of the tools, DeepSeek tends to write with a bolder voice, with more use of critical inferences and descriptive terms e.g. “retail colossus”, “ethical capitalism”, “betrays a reluctance”, Corporate evolution remains stunted”, “titan of tradition”.

In writing longer essays (5000-word), GPT-4o’s process is to create an outline, and then on its “Canvas” interface generate each section sequentially and ask for feedback step by step. This collaborative process facilitates co-writing.

GPT-4o: “The new essay document titled "How Technology is Reshaping Food Choices, Consumption Patterns, and the Future of Food Security" has been created and outlined. I’ll now begin writing the sections one by one with full academic depth and references. Would you like me to proceed with drafting the Introduction and Section I next?”

DeepSeek and CoPilot tend to be less effective in writing longer academic-style essays. Their language used is less sophisticated and the analysis is limited, even when prompted to write more in a in-depth manner and elaborate with more details.

-

The brands listed in this section are from the art project, “I’m Worth My Bread” – Singapore 2025 Case Study. There are altogether 35 brands – 33 of food products, and 2 of supermarket chains. For each brand, a 150-word description was generated, covering the brand and corporate development, key products, inventions or innovations, controversies and challenges.

List of brands:

1) Ayam Brand

2) Camel

3) Campbell's

4) Chilli Brand

5) Coca-Cola

6) DoDo

7) Eu Yan Sang

8) Ferrero

9) Glory

10) Irvins

11) Johnsonville

12) Kellogg's

13) Khong Guan

14) Kjeldsens

15) Maling

16) Mentos

17) Milo

18) Mitsuya

19) Myojo

20) Nescafe

21) Prima Taste

22) Quaker

23) Royal Umbrella

24) SCS

25) Seng Choon

26) Spring Home

27) Sun-Maid

28) Sunshine

29) Tiger

30) Toblerone

31) Tong Garden

32) Twisties

33) Yakult

34) Cold Storage

35) NTUC Fairprice

1) Ayam Brand

Founded in 1892 by French entrepreneur Alfred Clouet in Singapore, Ayam Brand is a pantry staple across Southeast Asia, best known for its canned sardines, tuna, and coconut products. Despite its name—drawn from the Malay word ayam, meaning “chicken”—the brand does not specialize in poultry. The name originated from the rooster emblem on its packaging, adopted at a time when pictorial branding aided recognition in largely illiterate markets. Over the decades, Ayam Brand expanded its product portfolio and regional presence, while maintaining manufacturing operations in Malaysia. The company has emphasized preservative-free ingredients and Halal certifications to cater to regional consumer preferences. However, it faces persistent challenges, including intense competition from global and local brands, fluctuating commodity prices, and consumer skepticism about the environmental impact of canned goods. While its longevity is notable, Ayam Brand must navigate shifting health trends and sustainability demands to remain relevant in a saturated and evolving food industry.

2) Camel

Emerging from a humble backyard in Singapore in 1974, Camel Nuts, founded by Mr. Poh Ah Seng and Mdm Ong Siew Hua, has grown into the nation's largest nut manufacturer. The company's expansion from small-scale roasting to large-scale production and distribution highlights the themes of convenience and affordability. The "Camel" name symbolizes financial resilience in Singapore's developing economy and brand recognition for a population with varying literacy levels. Camel Nuts offers a wide variety of roasted, salted, and flavored nuts, often packaged for on-the-go consumption, with a focus on flavor variations and enhanced shelf appeal. Facing competition from international and local brands, Camel Nuts maintains a functional and direct visual identity, and this often contrasts sharply and clearly with the predominantly more aspirational branding in the premium snack market. Its success is rooted in consistent accessibility and efficient production, rather than groundbreaking innovation or a strong, emotionally driven brand narrative.

3) Campbell’s

Campbell’s, founded in 1869 by Joseph A. Campbell and Abraham Anderson, became a cultural icon, especially after Andy Warhol’s 1960s pop art featuring its condensed soup cans. Over the years, the company expanded its product portfolio through acquisitions, including Pepperidge Farm, Prego, and V8, while diversifying beyond soups. However, this expansion led to operational complexities and brand dilution. In 2019, Campbell’s sold its Simple Meals and Shelf-Stable Beverage business in Australia and Asia Pacific, along with the Arnott's brand portfolio, to private equity firm KKR. This sale was part of the company’s ongoing efforts to streamline operations and refocus on core businesses. Despite its legacy, Campbell’s has struggled to keep pace with changing consumer preferences for healthier, more innovative products. The company now faces mounting competition from private-label brands and health-focused food companies, as it works to navigate these persistent challenges and maintain relevance in an increasingly competitive food market.

4) Chilli Brand

Chilli Brand, established in 1943 under People Bee Hoon Factory, specializes in rice vermicelli, a staple in Singapore’s diverse food culture. Known for its fine texture, the brand offers a variety of products, including the classic rice vermicelli, Fish Head, and Laksa versions. These cater to traditional dishes but also reflect the company’s ability to adapt to local consumer preferences and market demands. The introduction of its Healthier Choice Red Rice Vermicelli, made from red cargo rice, aims to address the growing demand for more nutritious food options. However, despite its long-standing presence, Chilli Brand faces significant competition in the crowded local food market. Changing consumer tastes, particularly the shift towards healthier and more sustainable foods, have presented challenges. While the brand remains a familiar name for many, the pressure to maintain product relevance amid modern trends persists, raising concerns about its ability to sustain market position in the future.

5) Coca-Cola

Conceived in 1886 by pharmacist John Pemberton as a medicinal syrup, Coca-Cola's trajectory embodies astute marketing and near-global ubiquity. Its early distribution through soda fountains laid groundwork for pervasive cultural presence worldwide. Key products, beyond the eponymous beverage, include a vast portfolio of sweetened drinks, reflecting an adaptive, if arguably health-compromising, corporate strategy. Innovation lies less in product shifts and more in branding, packaging, and distribution mastery, achieving one of the world's most extensive beverage networks. However, Coca-Cola has faced persistent criticism regarding its contribution to obesity and related health issues, alongside aggressive marketing tactics targeting vulnerable populations globally. Environmental concerns surrounding plastic waste and water usage in production also cast a shadow on its global operations. Despite these significant challenges and controversies, the brand's enduring iconography and remarkably effective advertising continue to shape consumer desires, a profound and complex testament to its carefully constructed, if critically examined, cultural significance.

6) DoDo

Founded in 1976 by Lim Boon Chay, DoDo began as a small fishball manufacturer in a kampung shed in Changi. Since its inception, the company has evolved into a key player in Singapore's seafood processing industry, specializing in fishballs, crabsticks, and yong tau foo. With large factories in Senoko (Singapore) and Malaysia, the company employs over 500 workers. In 2015, DoDo’s parent company, Thong Siek Holdings, sold a 55% stake to Neo Group, seeking to solidify its market position. However, DoDo’s growth has faced challenges, especially as it expands into new product categories like snacks. Despite efforts to diversify into products such as Crusty’s crab chips and breaded fish nuggets, questions remain regarding the long-term sustainability of its business model. Additionally, DoDo faces stiff competition from similar products in the market, with rival brands offering comparable seafood-based snacks, potentially impacting its market share, consumer brand loyalty, and long-term overall profitability.

7) Eu Yan Sang

Established in 1879 by Eu Kong, a migrant from Guangdong, Eu Yan Sang evolved from a modest dispensary in British Malaya. Upon Eu Kong's passing, his son Eu Tong Sen inherited the business, with later family shareholdings dispersed among his offspring. The company navigated listing, acquisition, delisting, and relisting. Great-grandson Richard Eu became CEO, overcoming family disputes. However, the family's control shifted with the full acquisition by a Japanese consortium of Mitsui and Rohto Pharmaceutical in 2024. Despite this evolution, the brand bridges heritage with modern retail, offering products from bird's nest to herbal remedies. Corporate expansion involved navigating diverse regulatory landscapes across Asia and Australia. The brand has faced scrutiny regarding the efficacy of some TCM products and ingredient sourcing. Eu Yan Sang's curated image of holistic wellness represents an ongoing negotiation between ancient wisdom and current market demands under new ownership, marking a new chapter for the firm.

8) Ferrero

Established in Alba, Italy, in 1946, Ferrero's journey from a small pastry operation to a global confectionery giant showcases a deliberate fusion of innovation and tradition. Pietro Ferrero's resourceful wartime use of hazelnuts to extend scarce cocoa led to Nutella, a pivotal product reshaping breakfast consumption. The Ferrero Rocher, with its hazelnut, wafer, and chocolate layers, exemplifies the brand's focus on textural and flavor interplay, consistently marketed as a premium, giftable indulgence. However, this polished image faces scrutiny. Allegations of child labor within cocoa supply chains and concerns over unsustainable palm oil sourcing present ethical challenges. A past investigation into potential hazelnut market dominance in Turkey offers a critical view of its corporate conduct. Despite these issues, Ferrero's consistent product quality and strategic acquisitions have solidified its market position, a testament to its enduring appeal and astute brand management within its tightly controlled, family-owned structure, still navigating complex ethical terrain.

9) Glory

Rooted in the Chin family's Peranakan culinary heritage since 1979, Glory Food emerged from Singapore, initially known for authentic sauces, most notably its Nonya Kaya, which gained early traction. This foundational commitment to traditional flavors provided a basis for the brand's later expansion into the competitive snack market with prawn crackers and fish crisps, also offering festive treats like pineapple tarts popular during celebrations. Innovation within Glory Food appears to follow subtle flavor development within existing product lines, rather than radical departures. Corporate growth has been characterized by a steady, regionally focused expansion, carefully navigating the inherent challenge of upholding culinary authenticity amidst numerous mass-produced alternatives. Significant public controversies appear absent, suggesting a consistent, if less overtly dynamic, approach to market engagement. Glory Food's enduring presence underscores a dedication to its heritage, though its artistic expression might be tempered by a pragmatic approach to a vibrant and evolving food industry.

10) Irvins

Emerging from a Singaporean seafood restaurant in 2008, Irvins swiftly established itself as a purveyor of intensely flavored, salted egg yolk-coated snacks. This focused product strategy, initially featuring fish skins and potato chips, fueled rapid regional expansion across Southeast Asia, effectively capitalizing on a novel and distinctly savory taste profile. The brand's deliberate and consistently applied bold yellow packaging facilitated immediate and pervasive visual recognition, quickly becoming ubiquitous in tourist-heavy areas. Innovation within the brand appears largely confined to the strategic application of its signature salted egg yolk coating to an expanding variety of snack bases, rather than fundamental or radical product reinvention. While its novelty generated consumer enthusiasm and trial, Irvins now confronts the imperative of sustained brand differentiation within an increasingly crowded snack market, adeptly navigating potential consumer fatigue with its core flavor profile and the proliferation of numerous, often lower-priced, imitators seeking to capitalize on its success.

11) Johnsonville

Co-founded in 1945 by Ralph and Alice Stayer in Wisconsin, Johnsonville evolved from a small butcher shop into a global sausage manufacturer while remaining privately held by the Stayer family. Its international ambitions took shape in 2015 with the acquisition of an 85% stake in Singapore-based Q.B. Food Trading, granting Johnsonville access to Southeast Asian markets and halal-certified production capabilities. The brand is known for its diverse portfolio of sausages, including bratwursts and breakfast links, and its commitment to proprietary spice blends. However, Johnsonville’s expansion has not been without significant setbacks. In April 2025, the company recalled over 22,000 pounds of cheddar bratwurst after reports of plastic contamination, raising concerns about quality assurance. As it navigates evolving global markets and shifting consumer expectations, Johnsonville’s trajectory illustrates the complex challenges of balancing growth with stringent safety and regulatory standards—while maintaining the identity and control characteristic of a long-standing, family-owned enterprise.

12) Kellogg’s

Established in 1906 by Will Keith Kellogg, the Kellogg Company, initially Battle Creek Toasted Corn Flake Company, shifted from sanitarium to global food conglomerate via aggressive marketing and product diversification. A significant 2023 restructuring placed its North American cereal business under WK Kellogg Co, focusing on iconic domestic brands. 1 Simultaneously, its international cereal and snack divisions now operate under Kellanova. Key products, like Corn Flakes and Frosted Flakes, prioritize mass appeal. Kellogg's has faced criticism for aggressively marketing sugary cereals to children, sourcing palm oil linked to deforestation, and notably, Froot Loops faced protests in the USA over artificial food dyes. Furthermore, early health claim and later "healthy" labeling controversies mark its history. The bifurcated entities, WK Kellogg Co and Kellanova, now face challenges adapting to health-conscious consumers and addressing public scrutiny regarding product formulations and corporate responsibility within a competitive market emphasizing wellness and transparent nutritional information globally.

13) Khong Guan

Established in Singapore in 1947 by brothers Chew Choo Keng and Chew Choo Han, Khong Guan Biscuit Factory (Singapore) Pte Ltd. emerged post-World War II, initially producing hand-made biscuits. Its subsequent expansion across Southeast Asia reflects a calculated corporate strategy for regional dominance and sustained market share. The brand's ubiquitous presence in regional supermarkets underscores its enduring and pervasive market penetration. Key products, such as the Cream Crackers and Marie biscuits, represent a consistent, if uninspired, product line with minimal fundamental innovation over decades. Challenges include navigating intense competition from multinational snack corporations and adapting to evolving consumer palates. While its nostalgic appeal remains potent for older demographics, the brand faces the imperative of modernizing its offerings and marketing to engage newer generations within a dynamic and increasingly diverse snack food landscape. Its long history, however, signifies a certain resilience within the regional market, despite limited product evolution and innovation.

14) Kjeldsens

Established in Denmark in 1926 by Anna and Marinus Kjeldsen, the family bakery evolved into the Kelsen Group A/S, also encompassing Royal Dansk. Holding a Royal Warrant of Appointment since 2009, its signature blue tins offer a consistent visual identity. Since its Hong Kong entry in 1963, facilitated by Roger Lobo, Kjeldsens became an iconic festive gift there. Kelsen Group has undergone several ownership changes, from its founding family to Incentive A/S, Campbell Soup Company (2013), and ultimately becoming part of the Ferrero-affiliated Fine Biscuits Company S.A. (2020). Key products remain traditional butter cookies with limited innovation. Challenges include butter price volatility and the prevalence of counterfeit products attempting to capitalize on its brand recognition, particularly during festive seasons. The brand's reliance on established recipes, while ensuring recognition, may limit adaptability. Its enduring presence, bolstered by royal endorsement, reflects a stable, if somewhat uninspired, yet largely predictable, brand management approach.

15) Maling

COFCO Maling, a subsidiary of COFCO (China Oil and Foodstuffs Corporation), and Shanghai Maling, under Bright Food Group, share origins in Shanghai Maling (1930), yet operate independently. COFCO, a state-owned enterprise, is a major force in China's food and agriculture sectors. Its vertically integrated production, leveraging state-backed distribution, distinguishes COFCO Maling from independent canned food manufacturers. COFCO’s historical role in early Chinese food exports underscores its national commercial importance. Distribution in Singapore is via local food distributor Yit Hong Pte Ltd. Yit Hong also distributes other COFCO brands, like Narcissus and Pearl River Bridge. In 2007, Singapore suspended two Chinese canned meat plants, including Maling and Narcissus, due to banned antibiotics, leading to stockpiling. The suspension lifted in late 2008, following Chinese factories sourcing frozen pork from Europe and the USA that met Singapore's regulations. The brand’s history, entwined with China’s industrial evolution, offers critical perspectives on regional food production.

16) Mentos

Mentos, a confectionary product first conceived by the Van Melle company, now known as Perfetti Van Melle following a 2001 merger, in the Netherlands in 1932, stands as an archetype of industrialised sweetness, presented in a meticulously engineered oblate spheroid form. Its construction features a yielding, sugary interior enrobed by a subtly resistant, glazed exterior. The formulation predominantly comprises refined sugars, glucose syrup, and hydrogenated vegetable oil, incorporating stabilising hydrocolloids such as gum arabic and gellan gum to ensure textural homogeneity across units. The brand's historical marketing strategies, ranging from the pervasive "Freshmaker" advertising campaigns to the scientifically demonstrable Mentos-Diet Coke geyser effect (a rapid effervescence triggered by the mint's micro-topography), illustrate methodology for consumer engagement. While available in a spectrum of flavour variations, the fundamental product persists as a testament to mass-produced, readily accessible sugary refreshment, its appeal grounded in its consistent, almost architectural, morphology and predictable sweet palatability.

17) Milo

Milo, a Nestlé product conceived in Australia by Thomas Mayne in 1934, functions as a globally distributed malted chocolate powder. Its production, involving spray-drying barley malt, milk solids, and cocoa, yields a distinct granular texture and a flavour profile differentiated by the malt component. Notably, its marketing prominently associates the beverage directly with sporting and athletic activities, cultivating an image of energy and vitality, particularly for younger demographics. Its formulation includes added vitamins and minerals, further reinforcing this perceived nutritional benefit. However, the brand has encountered significant criticism regarding its elevated sugar content, a point of contention that challenges its health-oriented marketing. Nonetheless, Milo enjoys widespread consumption across over 50 countries, signifying the successful propagation of a specific flavour profile and a culturally ingrained association with energy and childhood. The brand's history reveals the complex interplay between product formulation, marketing narratives, and evolving nutritional awareness in the global food landscape.

18) Mitsuya

Mitsuya Tasty Biscuit Sticks were started in 1978 by Calbee Moh Seng, formerly known as Moh Seng Marketing Pte. Ltd. Calbee Moh Seng distributes the brand. Mitsuya's focus remains largely on this single product, indicating a strategy of limited diversification. The biscuits are manufactured in Nagoya, Japan. Calbee Moh Seng began as the exclusive distributor of Calbee products and later became part of the Calbee Group, solidifying its position in the Singaporean market, a key and very profitable market for the company. The brand’s corporate development is very closely tied to Moh Seng's regional strategies, strongly emphasizing localized flavors and distribution networks. Mitsuya Tasty Biscuit Sticks are primarily sold in Singapore, with limited availability in other Southeast Asian countries. While not groundbreaking, the Mitsuya Tasty Stick offers a consistently consistent product in a market often driven by novelty. This stability can be viewed as both a strength and a weakness.

19) Myojo

Myojo, originally Myojo Shokuhin, marked an early entry into the instant noodle sector in Japan in 1950, utilizing flash-frying for swift noodle rehydration. The brand initially differentiated itself by offering traditional Japanese flavors, with Chicken Tanmen achieving lasting popularity, particularly in Singapore, where it became a staple. Demonstrating significant international expansion within the Southeast Asian market, Myojo established Singapore's inaugural instant noodle production facility in 1971, solidifying its regional presence following its market entry in 1970. Following its acquisition by Nissin Foods in 2006/2007, a strategic move in industry consolidation, Myojo became part of a larger global food enterprise. A notable food safety event in 2008 involved a product recall with Nissin due to insecticide contamination, raising consumer awareness regarding production standards. Similar to its competitors in the convenience food market, Myojo faces ongoing examination concerning the inherent nutritional characteristics of instant noodles, particularly sodium and processed ingredients. Scrutiny persists.

20) Nescafe

Nescafé, a flagship brand of Nestlé, was introduced in 1938 following research led by chemist Max Morgenthaler. Faced with a surplus of Brazilian coffee beans during the Great Depression, Nestlé developed a soluble coffee powder aimed at maximizing efficiency and durability. Over time, the brand’s portfolio expanded to include premium blends such as Nescafé Gold, ready-to-drink formulations, and single-serve systems. Its corporate trajectory reflects strategic diversification and broad market penetration. In Singapore, the brand was introduced in 1940, with early advertising confronting consumer skepticism regarding the quality of instant coffee. Despite its global reach, Nescafé has faced criticisms regarding environmental sustainability, supply chain ethics, and production consistency. Such challenges have pressured Nestlé to reevaluate aspects of its production and supply chain practices. Overall, the brand's evolution reflects an ongoing struggle to balance nostalgic appeal with modern market demands and ethical considerations, forming a complex legacy within the global coffee industry.

21) Prima Taste

Prima Taste, a Singaporean food brand established in the late 1980s, distinguishes itself by offering pre-packaged meal kits and sauces designed to replicate authentic local dishes such as Laksa and Hainanese Chicken Rice. Unlike mass-produced instant noodles or generic cooking sauces, Prima Taste's strategy hinges on the commodification of complex regional flavors. Its production processes, while industrialized, aim to preserve the aromatic and textural nuances of traditional cooking through concentrated pastes and specific ingredient pairings. Prima Taste is owned by Prima Food, a company with its origins in the flour milling business, starting in 1961. However, the brand's convenience comes at the cost of culinary authenticity and potential additives necessary for preservation and flavor enhancement in packaged formats. While achieving widespread international distribution, Prima Taste's products represent a mediated experience of Singaporean cuisine, a standardized interpretation for a globalized palate, distinct from the variability and artistry of hawker centre fare.

22) Quaker

Quaker, founded in 1877, is a leading American food brand known for its oatmeal, breakfast cereals, and snack products. Although it was a key player in the popularization of instant oatmeal, Quaker has faced criticism for its reliance on highly processed ingredients, refined grains, and added sugars in many of its products. Despite efforts to reduce sugar content in certain lines, many Quaker products still include artificial flavors, preservatives, and other processed components, raising concerns about nutritional value. The brand's expansion under PepsiCo’s ownership, following its acquisition in 2001, has broadened its portfolio to include snacks like granola bars and rice cakes. However, this expansion into mass-market snacks and beverages has led to debates about Quaker's ability to maintain a health-focused image amidst PepsiCo's profit-driven priorities. While Quaker continues to innovate, its position in the processed food sector faces challenges from health-conscious consumer trends and growing demands for organic ingredients.

23) Royal Umbrella

Royal Umbrella, a Thai rice brand prominent since its 1986 Singaporean introduction, specializes in premium Thai Hom Mali rice, emphasizing genetic purity and rigorous quality control from seed to packaging. Uniquely, the brand employs DNA fingerprinting technology to verify the authenticity and purity of its Hom Mali grains, a sophisticated practice setting it apart from many competitors in the global rice market. Owned by C.P. Intertrade Co., Ltd., the trading arm of the agricultural giant Charoen Pokphand (C.P.) Group, it leverages substantial corporate backing and distribution networks. A notable challenge occurred in 2013 with unsubstantiated toxic contamination claims, highlighting the brand's vulnerability to public perception and the rapid spread of misinformation. Despite its commitment to sustainability through initiatives like recyclable packaging and its distinctive focus on genetic verification, Royal Umbrella operates within an environment of heightened consumer awareness regarding food safety and traceability in the contemporary global food sector now.

24) SCS

SCS Butter, a long-established brand in Singapore's dairy industry, was originally linked to the Cold Storage company, but it has evolved independently over the years. In 2017, the brand underwent a significant redesign to modernize its image while maintaining its 112-year legacy. This rebranding aimed to attract a new generation of consumers while staying true to its traditional values. In 2019, DKSH Holdings (Malaysia) Berhad acquired Auric Pacific, the owner of SCS Butter, to strengthen its presence in the foodservice sector and expand its product portfolio. The acquisition provided DKSH with greater access to chilled and frozen products, helping it grow in the highly competitive market. Despite its established market position, SCS Butter faces challenges in adapting its traditional identity to evolving consumer demands. To remain relevant, the brand must balance its heritage with innovation while navigating the complexities of the changing dairy market and shifting consumer preferences over time.

25) Seng Choon

Seng Choon, a significant Singaporean egg producer founded in 1987 by Mr. Koh Swee Lai, a former pig farmer who transitioned to pioneer high-tech layer farming in Southeast Asia. Its vertically integrated operations, spanning feed production to distribution, mark a strategic consolidation ensuring considerable supply chain control, a notable advantage over smaller, fragmented farms. The farm commands an estimated 10-12% of the Singaporean egg market (circa 2019-2022). Its substantial scale, housing over 800,000 hens and producing around 600,000 eggs daily on its 36-acre facility, underscores its pivotal role in Singapore's food security and its adoption of advanced agricultural technologies for truly efficient production. However, a notable challenge arose in 2020 with a significant Salmonella outbreak linked to its eggs, leading to recalls and raising biosecurity concerns within such large-scale operations. This incident highlights the inherent vulnerabilities of intensive farming and potential public health implications in a densely populated urban context.

26) Spring Home

Spring Home, under Tee Yih Jia Food Manufacturing, represents the industrial evolution of traditional Asian foods. While the company began in 1969, its transformation accelerated in the 1980s following Sam Goi’s acquisition and automation of spring roll pastry production. Now producing up to 35 million sheets daily, Tee Yih Jia exports over 90% of its output to nearly 100 countries. Its portfolio spans roti paratha, samosas, and dim sum, with innovations like the frozen hargow crystal skin—a mechanized version of a once hand-crafted item. However, the brand’s global expansion has surfaced challenges. In 2020, Spring Home products were recalled across several markets due to undeclared milk allergens, raising regulatory and quality control concerns. The COVID-19 pandemic further exposed vulnerabilities in its foodservice-reliant distribution model. Spring Home’s journey underscores the persistent tension between scaling traditional cuisine and preserving its cultural and artisanal integrity amid industrial pressures and global market demands.

27) Sun-Maid

Sun-Maid Growers of California, founded in 1912 as the California Associated Raisin Company, is a cooperative representing around 850 family-owned farms. It industrialized raisin processing and became synonymous with its 1915 “Sun-Maid Girl” emblem—one of the most iconic images in U.S. food branding. From its vast Kingsburg facility, the company processes over 200 million pounds of raisins annually and exports to more than 60 countries. Beyond classic raisins, its product range includes yogurt-covered varieties, sour raisin snacks, and other dried fruits, reflecting attempts to modernize appeal. Yet, Sun-Maid's legacy is not without complications. The cooperative model faces economic pressures, while the labor-intensive nature of grape harvesting in California's Central Valley continues to draw scrutiny, particularly regarding seasonal labor practices. Moreover, shifts in consumer preferences toward fresh produce and alternative snacks pose ongoing strategic challenges. Sun-Maid’s evolution illustrates the delicate balance between tradition, industrial agriculture, and changing global food economies.

28) Sunshine

Sunshine Bakeries, established in Singapore in 1930, has been a significant player in the nation's commercial baking industry. In the 1970s, it was among the first to introduce plastic packaging for bread, enhancing shelf life and hygiene standards. Its product line includes wholemeal breads, low glycemic index options, and cream rolls, catering to diverse consumer preferences. Despite early success, Sunshine faced challenges, including increased competition and shifting consumer tastes. In the 1990s, it exited the Malaysian market temporarily due to declining performance but has since re-entered with efforts to regain footing. Today, Sunshine operates under Auric Pacific Group Limited, a Singapore-based food and beverage company. Auric Pacific manufactures and distributes brands such as Sunshine bread, SCS butter, and Buttercup, all holding strong positions in Singapore and Malaysia. The company has undertaken rationalization initiatives to restore profitability, reflecting broader market pressures and the evolving nature of the regional baked goods industry.

29) Tiger

Tiger Beer, launched in 1932 by Malayan Breweries (a joint venture between Heineken and Fraser and Neave), became Southeast Asia’s first locally brewed lager, marketed for tropical climates. Allied forces during WWII entrenched its regional dominance. Post-1965 independence, canned editions aligned with Singapore’s industrial modernization. Rebranded as Asia Pacific Breweries (APB) in 1990, expansion into Vietnam, China, and India targeted emerging middle-class consumers. Campaigns like 2014’s “Uncage” emphasized edgy aesthetics to court youth but faced critiques of substituting branding for product innovation. Despite a 1998 “World’s Best Lager” award, reliance on legacy recipes and regional variants revealed stagnation in saturated markets. Heineken’s 2012 full acquisition heightened tensions: marketed “Asian authenticity” clashed with Dutch multinational control. APB’s trajectory reflects postcolonial paradoxes—its heritage commodified under global capitalism, strained between nostalgia and homogenization. Once symbolizing industrial progress, Tiger Beer's historical legacy is overshadowed by market skepticism toward corporate stewardship and creative inertia.

30) Toblerone

Established in Bern, Switzerland, in 1908 by Theodor Tobler and Emil Baumann, Toblerone swiftly gained recognition for its unique triangular prism packaging and its distinct honey-almond-nougat chocolate. Initially independent, the brand's ownership evolved through mergers with Suchard (1970), then Jacobs coffee (1982) to become Jacobs Suchard, before acquisition by Kraft Foods (1990) and ultimately Mondelēz International (2012). While the Matterhorn silhouette cemented its Swiss identity, its partial production shift to Bratislava, Slovakia, from 2022 alongside Swiss manufacturing, caused its removal from some packaging due to Swiss regulations on national symbols. Key products remain variations of the original bar, with innovation primarily in size and flavor. A 2016 widening of chocolate peaks as a cost-saving measure drew considerable consumer criticism regarding perceived value reduction. Despite its iconic, legally protected shape, Toblerone faces challenges maintaining premium status amid fluctuating costs and ethical consumer demands under successive corporate ownership and increasingly multinational production.

31) Tong Garden

Started in Singapore in 1963 by Ong Tong Guan, Tong Garden's initial focus on groundnut processing belies a complex trajectory marked by both expansion and internal strife. Its regional expansion across Southeast Asia, with manufacturing facilities in multiple countries, masks a significant 2019 family dispute between the founder's children, the group's shareholders, involving allegations of business diversion and trademark transfer. This legal contention highlighted intricate internal power dynamics and familial governance challenges within leadership. Key products, a wide array of nuts and snack mixes in distinctive green packaging, represent incremental innovation, primarily in flavour variations. Geographically, Tong Garden has established operations and market presence across Southeast Asia and beyond, reaching over 35 countries. While achieving regional market presence, brand's history reveals vulnerabilities tied to familial control and succession planning among the founder's descendants. Its enduring legacy is thus intertwined with both entrepreneurial success and significant internal conflict amongst its shareholders.

32) Twisties

Twisties, a corn-based extruded snack introduced in Australia in 1950, has become a familiar presence in Singapore’s snack landscape. While originating from Australia—developed by Isador Magid and later acquired by The Smith’s Snackfood Company (now under PepsiCo)—Twisties in Southeast Asia is manufactured and distributed by Mondelēz International. This arrangement followed Kraft Foods’ 2012 corporate split, which placed various global snack brands under Mondelēz’s portfolio. Though it shares a similar name with Malta’s Twistees, the two are unrelated brands with distinct origins. In Singapore, Twisties is widely recognised for its bold, nostalgic flavours like Cheese and BBQ Curry. In Australia, experimental launches such as “Chickeese” and “Caviar” have stirred consumer curiosity and critique, but these flavours have not reached Singapore shelves. Locally, Twisties competes with both global imports and an expanding field of regional snack brands. Its sustained popularity reflects both brand longevity and evolving taste preferences in Singapore.

33) Yakult

Developed in Japan in 1935 by microbiologist Minoru Shirota, Yakult's foundation rests on a specific Lactobacillus casei Shirota strain, purportedly offering health benefits. Its chilled, dairy-based probiotic drink, requiring refrigeration, was introduced to Singapore in 1979, mirroring its global reach via the "Yakult Lady" system. Notably, in Singapore, it has consistently faced direct competition from Vitagen. Key products in Singapore are original and localized flavored probiotic drinks. Innovation there includes unique fruit-flavored family packs. Challenges involve ongoing scientific substantiation of health claims and addressing sugar content concerns within a competitive market. The company faced corporate scandals involving alleged financial mismanagement in the 1990s and a reported racketeer payoff in 2002, significantly impacting its corporate image and raising ethical questions. Despite widespread consumption and unique marketing, Yakult's history reveals a tension between its health-focused image and corporate malfeasance, requiring scrutiny of its operational ethics and tangible benefits of its core offering.

34) Cold Storage

Cold Storage, a longstanding pillar of Singapore’s retail scene since 1903, initially distinguished itself with innovations such as air-conditioned supermarkets and a focus on imported, premium goods. Once part of Dairy Farm International (DFI) Retail Group, the chain reflected an upmarket consumer orientation. However, by March 2025, shifting consumer preferences, rising competition, and operational inefficiencies prompted a major divestment. DFI agreed to sell 48 Cold Storage outlets, 41 Giant stores, and two distribution centers in Singapore to Malaysia-based Macrovalue for S$125 million. This followed Macrovalue’s acquisition of Cold Storage and Giant operations in Malaysia in 2023, signaling its broader regional expansion strategy. The transaction highlights broader transformations within Singapore’s grocery industry, including the rise of e-commerce and budget-oriented shopping behavior. Whether Cold Storage can preserve its legacy under new ownership remains uncertain, as balancing heritage branding with cost-efficiency and scalability will pose critical structural challenges in an evolving retail ecosystem.

35) NTUC Fairprice

NTUC FairPrice, founded in 1973 as NTUC Welcome, was established by Singapore’s labour movement to combat profiteering and rising costs during inflationary times. Its first outlet in Toa Payoh marked the beginning of a public-sector effort to stabilise grocery prices through cooperative ownership. By 1983, a merger with the Singapore Employees Cooperative led to the formation of NTUC FairPrice Co-operative Limited. It diversified into retail formats such as FairPrice Finest, FairPrice Xtra, and Cheers stores, aiming to meet evolving consumer demands. Despite efforts to modernise—such as introducing self-checkout systems—these changes have occasionally received mixed responses, particularly among older customers. The creation of the FairPrice Foundation in 2008 signaled continued community investment. However, growing pressure from e-commerce competitors and private-label retailers prompts questions about its adaptability. FairPrice's dual identity as a commercial entity and social enterprise remains both its strength and a strategic constraint in a fast-changing retail environment.

-

This section contains essays on topics related to the project. The AI platforms were used to generate 5000-word essays in an academic style. The topics are as follows:

Food supply and technology, and the rise of countries and companies

Standardization and authenticity in the propagation of food culture in a globalized system

How technology is reshaping food choices, consumption patterns and the future of food security

Food canning – its invention and influence on the food industry, global supply chains and food culture

Food history and cultural research using AI

The relevance and influence of Gross Domestic Product (GDP)

Singapore, a 60-Year-Old Nation State

Topic A. Food supply and technology, and the rise of countries and companies. Explore how food supply and technology, from agricultural innovations and supply chain management to digital marketplaces and food processing techniques, have impacted countries’ economic development and multinational company growth. Include interesting examples in the past 100 years, and include an analysis of Singapore.

Author: Gemini 2.0 Flash

Title: Food Supply and Technology, and the Rise of Countries and Companies

(5,430 words)

I. Introduction

The intricate and often symbiotic relationship between a nation's capacity to secure its food supply, the dynamism of its technological innovation, and its subsequent trajectory of economic ascendancy constitutes a fundamental and enduring narrative throughout the annals of human history. From the earliest, rudimentary agricultural practices that marked the Neolithic Revolution to the highly sophisticated and globally interconnected food networks that characterize the contemporary era, a society's fundamental ability to adequately nourish its populace and to effectively harness the transformative power of advancements in food production, processing methodologies, and distribution systems has consistently served as a pivotal and often decisive determinant of its overall prosperity, its internal stability, and its relative influence within the broader global landscape. Over the course of the preceding century, this critical nexus between food security, technological progress, and economic development has intensified with remarkable and unprecedented rapidity, with groundbreaking technological breakthroughs acting as exceptionally potent catalysts not only for the accelerated economic development of individual countries, both large and small, but also for the expansive and often transformative growth of multinational corporations that operate across increasingly intricate global value chains.

The historical record is replete with compelling examples of how pivotal agricultural innovations, ranging from the adoption of the plow and the development of irrigation systems in antiquity to the more recent breakthroughs in synthetic fertilizers and genetically modified crops, have fundamentally reshaped societal structures and propelled economic growth. Similarly, advancements in food preservation techniques, from simple drying and salting to the sophisticated methods of canning and freezing, have not only reduced food waste and extended shelf life but have also facilitated the emergence of complex trade networks and the rise of commercial enterprises dedicated to food distribution. In the modern era, the integration of information technology and advanced logistics has further revolutionized the food supply chain, creating unprecedented efficiencies and enabling the global reach of food products.

This article undertakes a comprehensive and nuanced exploration of the multifaceted ways in which the intertwined forces of food supply and technology, encompassing a broad and interconnected spectrum from foundational agricultural innovations and increasingly sophisticated supply chain management practices to the transformative impact of digital marketplaces and the continuous evolution of advanced food processing techniques, have profoundly shaped the economic trajectories of nations across diverse developmental stages and have simultaneously fueled the remarkable expansion of multinational companies operating within the global food system. Through a meticulous examination of salient historical examples spanning the last hundred years, a period marked by unprecedented technological progress and globalization, and complemented by a focused and in-depth analysis of Singapore's distinctive developmental path from a food-vulnerable newly independent state to a recognized global hub for food innovation and resilience, this inquiry aims to elucidate the dynamic and often complex interplay between these critical forces and their enduring and evolving significance within the contemporary global landscape. By dissecting the specific technological advancements, the strategic policy choices of nations, and the entrepreneurial endeavors of corporations, this study seeks to provide a comprehensive understanding of how food supply and technology have become inextricably linked to the economic fortunes of countries and the global reach of businesses in the 21st century.

II. The Foundational Role of Agricultural Innovations (Early to Mid-20th Century)

The early to mid-20th century witnessed a series of transformative agricultural innovations that established a crucial foundation for subsequent economic shifts. The increasing mechanization of farming practices, coupled with the groundbreaking development of synthetic fertilizers and the introduction of chemical pesticides, collectively resulted in a substantial augmentation of agricultural productivity across numerous regions of the world. The widespread adoption of tractors and other sophisticated machinery gradually supplanted manual labor, thereby facilitating large-scale agricultural operations and significantly enhancing overall efficiency. In the United States, for instance, the proliferation of tractors on farms during the first half of the 20th century experienced exponential growth, leading to notable increases in output per worker and a discernible transition towards more extensive, commercially oriented agricultural enterprises (Olmstead and Rhode 15-17). This enhanced efficiency not only secured domestic food supplies but also generated surpluses amenable to international trade, thereby contributing positively to national income. Similarly, nations such as Canada and Australia, endowed with vast expanses of arable land, reaped considerable benefits from agricultural mechanization, establishing themselves as major global exporters of grains and other essential commodities (Pomfret 187-89).

A particularly seminal technological breakthrough in the realm of food production was the industrial synthesis of ammonia through the Haber-Bosch process in the early 20th century. This pivotal innovation enabled the mass production of nitrogen-based fertilizers, which profoundly impacted crop yields by effectively replenishing vital soil nutrients (Smil 19-23). The widespread application of synthetic fertilizers in countries like Japan and various parts of Europe played a crucial role in their agricultural recovery and subsequent economic growth during both the interwar and post-war periods. Notably, companies such as BASF in Germany assumed a central role in the production and distribution of these essential fertilizers, marking an early and significant stage in the ascent of multinational agrochemical corporations. Concurrently, the development of synthetic pesticides, exemplified by the introduction of DDT in the 1940s, provided novel tools for the effective control of pests and diseases that had historically inflicted significant damage on agricultural crops. While later encountering environmental scrutiny, these early pesticides substantially mitigated crop losses and further contributed to heightened agricultural output (Carson 27-32). Companies such as Dow Chemical and Monsanto began to emerge as key players in the development and commercialization of these agricultural chemicals, establishing extensive international distribution networks to facilitate their global reach. These foundational agricultural innovations not only bolstered food security within the nations that readily adopted them but also generated significant opportunities for countries possessing agricultural surpluses to engage in lucrative international trade, thereby strengthening their national economies. Moreover, the very technologies themselves spurred the growth of nascent multinational companies actively involved in the manufacturing and global distribution of agricultural machinery, synthetic fertilizers, and chemical pesticides.

III. World War II and the Dawn of Post-War Opportunities for Multinational Companies in Food and Technology

As previously delineated, the period encompassing World War II and its immediate aftermath served as a critical juncture, unexpectedly catalyzing technological advancements and precipitating significant shifts in the global economic landscape. This confluence of factors created a particularly fertile environment for the expansive growth of multinational companies operating within the food supply and technology sectors. The exigencies of wartime necessitated rapid technological innovation, yielding advancements in crucial areas such as food preservation and transportation. Refinements in dehydration and canning techniques, initially developed to efficient sustenance for military personnel, subsequently found widespread civilian applications, significantly extending the shelf life of food products and facilitating their distribution across increasingly wider markets (UpKeep). Similarly, notable improvements in refrigeration technology, essential for maintaining military supplies, became progressively more accessible for both commercial and domestic utilization, thereby fundamentally transforming food storage practices and enabling the growth of industries heavily reliant on perishable goods.

Furthermore, the United States emerged from the global conflict as a dominant economic power, possessing an industrial infrastructure that remained largely intact. The establishment of the Bretton Woods system played a pivotal role in facilitating international trade, and a substantial surge in post-war consumer demand created unprecedented market opportunities (Investopedia). American companies, benefiting from their technological advantages and access to substantial capital, were strategically positioned to capitalize on this burgeoning demand, both within the domestic market and across international borders. The post-war era witnessed the rapid growth and internationalization of numerous companies that astutely leveraged wartime technological advancements and effectively catered to the evolving needs and preferences of the post-war consumer landscape. Iconic brands such as Campbell Soup Company and Nestlé significantly expanded their offerings of canned and processed food products, effectively meeting the escalating demand for convenient meal solutions in rapidly suburbanizing societies. Coca-Cola, indelibly linked to American cultural influence during the war, aggressively expanded its global network of bottling and distribution facilities, becoming a ubiquitous symbol of global consumerism (CFR). PepsiCo also embarked on a trajectory of significant international growth during this period, directly competing with Coca-Cola for global market share within the rapidly expanding soft drink industry. Companies such as Frigidaire adeptly capitalized on advancements in refrigeration technology to effectively meet the burgeoning demand for household appliances that revolutionized food storage and preparation within the modern post-war home (History.com). Tupperware, ingeniously utilizing plastic innovations developed during the war, revolutionized food storage through its innovative airtight containers, effectively marketed through a novel and empowering direct-selling strategy that engaged women within the domestic sphere (PBS). Agricultural machinery giants, including John Deere and International Harvester, significantly expanded their global sales operations, thereby supporting the increasing mechanization of agricultural practices worldwide. Simultaneously, agrochemical companies such as Dow and Monsanto further developed and aggressively marketed synthetic fertilizers and pesticides, significantly contributing to the intensification of agricultural practices on a global scale (Science History Institute).

IV. The Green Revolution and its Global Impact (Mid to Late 20th Century)

The Green Revolution, a transformative period of agricultural research, development, and technology dissemination that spanned from the 1940s to the late 1970s, exerted a profound and multifaceted influence on global food production and the subsequent trajectory of economic development in numerous nations, particularly in the developing world. This concerted effort, largely spearheaded by the groundbreaking work of individuals like Nobel laureate Norman Borlaug and supported by international organizations and philanthropic foundations, focused on a paradigm shift in agricultural practices centered around the cultivation of high-yielding varieties (HYVs) of staple crops, notably wheat, rice, and maize. These newly developed varieties possessed genetic modifications that made them more responsive to fertilizers and irrigation, and often had shorter growing seasons, allowing for multiple cropping cycles within a single year. The successful implementation of these HYVs, however, was intrinsically linked to the adoption of a comprehensive package of modern agricultural inputs and techniques, including the strategic application of synthetic fertilizers and chemical pesticides to maximize yields and protect crops from pests and diseases, as well as the implementation of improved irrigation infrastructure and more efficient water management practices (Evenson and Gollin 587-93).

The impact of the Green Revolution on the economic development of many developing economies was substantial and far-reaching. Countries like India and Mexico, which were among the early and enthusiastic adopters of Green Revolution technologies, witnessed remarkable and often unprecedented increases in their production of essential food grains. This dramatic surge in agricultural output played a crucial role in enabling these nations to achieve greater levels of food security for their rapidly growing populations and significantly reduce their historical reliance on often volatile international food imports. The positive ripple effects of this agricultural expansion extended throughout their broader economies, generating new employment opportunities in rural areas, stimulating growth in related industries such as agricultural machinery and input supply, and contributing significantly to overall national economic development (Hazell 477-79). The increased availability of affordable food also had positive social implications, contributing to improved nutrition and public health outcomes in many regions that benefited from the Green Revolution.

However, the Green Revolution was not without its complexities and criticisms. The increased reliance on monoculture farming of HYVs raised concerns about the loss of valuable biodiversity and the potential vulnerability of agricultural systems to widespread disease or pest outbreaks. Furthermore, the intensive use of chemical fertilizers and pesticides led to environmental concerns regarding soil degradation, water pollution, and potential health risks. The economic benefits of the Green Revolution were also not uniformly distributed, with larger farmers often better positioned to adopt the new technologies and inputs compared to smallholder farmers, potentially exacerbating existing social and economic inequalities in some regions (Shiva 60-65). These multifaceted consequences underscore the intricate interplay between technological advancement, economic development, and the critical need for sustainable and equitable implementation strategies in the agricultural sector.

V. The Transformation of Food Processing and Supply Chains (Late 20th Century to Present)

The latter decades of the 20th century and the early 21st century witnessed a profound reshaping of food processing technologies and a significant increase in the complexity and reach of global food supply chains. These intertwined transformations have had a substantial impact on both the economic development of nations and the expansive growth of multinational food corporations, enabling them to introduce novel products, access previously unreachable markets, and optimize their operations on a global scale.

One of the most significant drivers of this transformation was the development and widespread adoption of advanced food processing technologies. Ultra-High Temperature (UHT) processing, for instance, revolutionized the dairy and beverage industries by allowing milk and juices to be shelf-stable for extended periods without refrigeration. This technology enabled companies like Parmalat (Italy) to expand their distribution networks across countries with less developed cold chain infrastructure, reaching consumers in emerging markets who previously had limited access to fresh dairy products. Similarly, advancements in modified atmosphere packaging (MAP), which controls the gases within a food package to slow spoilage, allowed companies dealing with fresh produce, such as Dole and Chiquita, to extend the shelf life of their fruits and vegetables, facilitating longer transit times and access to more distant markets in Europe and Asia.

The development of freeze-drying technology, initially utilized during World War II for military rations, found commercial applications in the post-war era, leading to the creation of instant coffee by companies like Nestlé with their Nescafé brand. This innovation not only offered convenience to consumers but also allowed Nestlé to distribute coffee globally without the constraints of spoilage associated with fresh or traditionally processed coffee beans. Spray-drying, another technology refined during the war, became crucial for the production of powdered milk and instant soups, enabling companies like Unilever (with brands like Knorr) to offer affordable and convenient meal solutions in diverse markets with varying levels of infrastructure.

The frozen food industry experienced exponential growth due to advancements in flash freezing techniques, pioneered by Clarence Birdseye. This method preserved the quality and nutritional value of foods more effectively than earlier freezing methods. The introduction of "TV dinners" by companies like Swanson in the 1950s, featuring pre-portioned frozen meals, catered to the burgeoning demand for convenience in post-war Western societies and laid the foundation for a vast global market for frozen prepared foods. Companies like McCain Foods (Canada) capitalized on this trend, expanding internationally with frozen French fries and other potato products, becoming a global leader in the frozen food sector.

Furthermore, innovations in extrusion technology allowed for the creation of new textures and forms in food products, leading to the development of breakfast cereals by companies like Kellogg's and General Mills, which were then marketed globally as convenient breakfast options. The development of new food additives, such as emulsifiers and stabilizers, improved the texture and shelf life of processed foods, enabling companies to create consistent products that could be distributed and sold across diverse geographical regions and under varying environmental conditions.

The rise of sophisticated logistics and transportation technologies was equally critical in the transformation of food supply chains. The advent of refrigerated shipping containers in the mid-20th century revolutionized the international trade of perishable goods, allowing for the efficient and safe transport of meat, dairy, fruits, and vegetables across vast distances. This enabled countries like New Zealand and Chile to become major exporters of agricultural products to markets in North America and Europe. Companies specializing in logistics, such as Maersk and DHL, played a crucial role in facilitating these complex global movements of food products.

The integration of information technology in supply chain management further optimized efficiency and reduced costs. Early forms of inventory management systems evolved into sophisticated enterprise resource planning (ERP) software, allowing multinational food companies to track inventory, manage production schedules, and coordinate distribution across their global networks. This enabled companies to respond more effectively to consumer demand and to manage the complexities of sourcing ingredients and distributing finished products across diverse international markets.

In summary, the transformation of food processing and supply chains in the late 20th and early 21st centuries was characterized by a synergistic interplay of technological innovations in food preservation, processing, and transportation, coupled with advancements in information management. These developments enabled multinational food companies to create new product categories, extend the shelf life of existing products, access previously inaccessible markets, and optimize their global operations, profoundly shaping the landscape of the global food industry and influencing dietary patterns worldwide.

VI. The Digital Revolution and the Future of Food (21st Century)